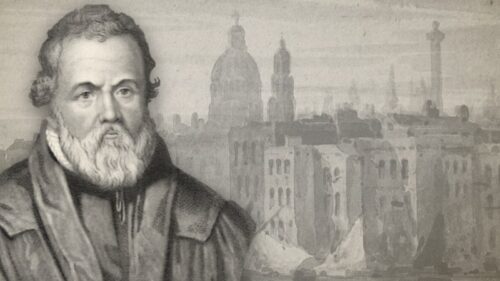

The Life And Martyrdom Of John Bradford

The Sower 1880:

“By the grace of God I am what I am.” These words were penned by one who had fully learned their meaning. This was no mere theoretical statement on the part of the Apostle, but a free and frank confession, based upon a deep and tried experience, that he was a debtor to the free and sovereign grace of God. Once he was a persecutor of the followers of Jesus of Nazareth, incessantly occupied in haling men and women to prison; and, when he penned these words, the Apostle was thoroughly satisfied that, but for the grace of God, he would have continued this bloodthirsty career unto the day of his death. But he was mercifully arrested as he was on an errand of persecution. The eyes of his understanding were opened, and he was enabled to see that the truths he had so keenly opposed were the verities of the Gospel, and the people he had persecuted were the people of God. The Apostle Paul was from that day a changed man. His career, his employment, his companions, all were changed. The doctrines he had tried to extinguish he now blazed abroad, and the people he had sought to crush he now edified and comforted. Abandoning his bloodthirsty work, he became henceforward a preacher of the Gospel, labouring “more abundantly than they all; yet,” continues the Apostle, ”not I, but the grace of God which was with me.” “What a grand—what a wonderful—transition in the character and pursuits of the man! Paul felt it to be so, and he ascribed its accomplishment not to any virtue or power inherent in himself or in any other creature, but solely and entirely to free grace. “By the grace of God I am what I am.” Bradford, the martyr, also made a similar confession, and thus coincided with the Apostle Paul in ascribing all temporal and spiritual blessings to the free and sovereign favour of the Almighty. On one occasion, as a criminal was passing on to execution, the illustrious martyr, pointing to the prisoner, exclaimed, “There goes John Bradford, but for the grace of God!” This was the preventive and restraining power that stopped him in a career of sin and folly, curbed his lusts and passions, and enabled him to “choose the better part.”

Although they lived at very distant periods in the world’s history both Apostle and martyr were solemnly assured that the grace of God was the primary source of all spiritual blessings. By the grace of God both of them were brought, under the teaching of the Holy Spirit, to know and feel their misery as sinners, and their consequent need of mercy; and by the grace of God they were enabled to believe with that faith which is the gift of God that Jesus Christ had paid the penalty due to their transgressions, and that their sins were washed away in the blood of the Lamb. “By grace are ye saved, through faith; and that not of yourselves: it is the gift of God: not of works, lest any man should boast.” Both these eminent saints were debtors to free grace alone, and they were ever ready to acknowledge it, to the humbling of the creature and the praise of their Creator and Redeemer.

Manchester was the birthplace of John Bradford. The citizens of this large and populous city are reminded of this fact by a statuette of the martyr which adorns a portion of the exterior of that imposing edifice, the new Town Hall. After receiving a good education, we find him, in the days of Henry VIII, secretary to Sir John Harrington, who was treasurer of the king’s camps and buildings at Boulogne.

On account of his ability as a scribe, and his expertness at figures, Bradford gained the favour of his master, and became his confidential adviser in all weighty matters. A very good prospect appeared to lay before him. But a sudden change passed over the mind of the secretary, which caused him to resign his post, return to his native land, and preach the Gospel. Bradford at once proceeded to the university of Cambridge, and earnestly set to work at the prosecution of his studies; and his diligence was attended with such success that, after a few years’ residence, the degree of Master of Arts was bestowed upon him. Another honour awaited him. But a short time elapsed before the Master and Fellows of Pembroke Hall offered him a Fellowship in their college, and Bradford was now considered one of the luminaries of the university.

During his residence in Cambridge, one of his dearest and most intimate friends was Martin Bucer. This worthy man had perceived that Bradford was not only a diligent and learned scholar, but a humble and sincere Christian, and one well qualified to proclaim the grand and majestic truths of the Gospel. Bucer would often suggest this matter to his friend, but Bradford’s natural shyness and reserve would at once discourage the idea. But Bucer became more pressing, and would continually revert to the subject, urging Bradford to go forward as a preacher of the Gospel. Bradford shrunk from the task—not because he feared to declare the Gospel of the grace of God, but the solemn responsibility of the post awed him. On one occasion he pleaded his meagre learning—a rather ungrounded plea—as an excuse for not daring to preach the Word. But Bucer’s answer was to the point. “If,” said this good man, “thou hast not fine wheat bread, yet give the poor people barley bread, or whatsoever else the Lord hath committed unto thee.” At length Bradford yielded; and Dr. Ridley, who was then Bishop of London, gave him a prebend in St.. Paul’s Cathedral, where he diligently laboured for three years.

But the liberty of preaching the Gospel enjoyed in King Edward’s days was shortlived, for, very soon after the accession of Queen Mary, those who had been most diligent and prominent in this gracious work were thrown into prison. Bradford was among the number. On August 16th, 1553, he was incarcerated in the Tower, and he was imprisoned from that time in various places of confinement until the month of January, 1555. During that long period he was variously employed. One day he would be arguing with some friar who had been sent to harass him; and the next day he might devote to the compilation of some sweet and edifying epistle to those who needed “building up in their most holy faith.” At other times he would be engaged in prayer or study. Although a prisoner, Bradford was not idle. Many and constant were the discussions he had with his adversaries, and at these trying times he would preserve a surprising equanimity, and answer their questions in a concise and scholarly manner. Bradford must have possessed a remarkably calm mind and good temper, for it is difficult to discover the least ruffle or sign of discomposure in the many long discussions he had with his crafty and malicious foes. It is not our intention, however, to follow our illustrious hero through all these debates with bishops, friars, and others, so we have selected one short discussion as a sample of the whole.

During the confinement of Bradford in the Compter in London, he was visited by the Archbishop of York and the Bishop of Chichester. These two prelates behaved very kindly to him. After commending his godly life, the Archbishop of York told Bradford that, actuated by pure motives of love, he had come to confer with him on the weighty matters of religion. The arch- bishop then asked him the following question—“How he was certain of salvation and of his religion?”

Bradford, after thanking him for his kindness and good wishes, replied, “By the Word of God, even by the Scriptures, I am certain of salvation and religion.”

YORK: “Very well said; but how do you know the Word of God and the Scriptures but by the Church?’’

BRADFORD: “Indeed, my lord, the Church was and is a means to bring a man to know the Scriptures and the Word of God, as the woman of Samaria was the means by which the Samaritans knew Christ; but, when they heard Him speak, they said, ‘Now we know that He is Christ, not because of thy words, but because we ourselves have heard.’ So, after we come to the hearing and reading of the Scriptures showed unto us and discerned by the Church, we do believe them and know them as Christ’s sheep, not because the Church saith they are the Scriptures, but because they be so, being assured thereof by the same Spirit who wrote and spoke them.”

YORK: “You know in the Apostles’ time at first the Word was not written.”

BRADFORD: “True, if you mean it for some books of the New Testament; but else for the Old Testament, St. Peter tells us, ‘We have a more sure word of prophecy.’ Not that it is simply so, but in respect of the Apostles, which being alive and subject to infirmity, attributed to the written Word more weight, as wherewith no fault can be found; whereas for the infirmity of their persons men perchance might have found some fault at their preaching; although in very deed no less obedience and faith ought to have been given to the one than to the other, for all proceedeth from one Spirit of truth.”

YORK: “That place of St. Peter is not to be understood of the Word written. You know that Trenreus and others do magnify much, and allege the Church against the heretics, and not the Scriptures.”

BRADFORD: “True, for they had to do with such heretics as denied the Scriptures, and yet did magnify the apostles; so that they were forced to use the authority of those Churches wherein the apostles had taught, and which had still retained the same doctrine.”

Here the Bishop of Chichester interposed by saying to Mr. Bradford, “You speak the very truth; for the heretics did refuse all Scriptures, except it were a piece of Luke’s Gospel.”

To this the martyr replied, “Then the alleging of the Church cannot be principally used against me, which am so far from denying of the Scriptures that I appeal to them utterly as to the only judge.”

YORK: “A pretty matter, that you will take upon you to judge the Church! I pray you, where hath your Church been hitherto, for the Church of Christ is Catholic and visible hitherto?”

BRADFORD: “My lord, I do not judge the Church when I discern it from that congregation and those which be not the Church; aud I never denied the Church to be Catholic and visible, although at some times it is more visible than at others.”

CHICHESTER: “I pray you tell me where the Church which allowed your doctrine was these four hundred years?”

BRADFORD: “I will tell you, my lord, or rather you shall tell yourself, if you will tell me this one thing—where the Church was in Elias’s time, when Elias said that he was left alone?’’

CHICHESTER: “That is no answer.”

BRADFORD: “I am sorry that you say so; but this will I tell your lordship, that, if you had the same eyes wherewith a man might have espied the Church then, you would not say it were no answer. The fault why the Church is not seen by you is not because the Church is not visible, but because your eyes are not clear enough to see it.”

CHICHESTER: “You are much deceived in making this collation betwixt the Church then and now.”

YORK: “Very well spoken, my lord; for Christ said, ‘I will build My Church;’ and not ‘I do,’ or ‘I have built it,’ but ‘I will build it.'”

BRADFORD: “My lords, Peter teacheth me to make this collation, saying, as in the people there were false prophets, which were most in estimation before Christ’s coming, so shall there be false teachers among the people after Christ’s coming, and very many shall follow them; and, as for your future tense, I hope your grace will not thereby conclude Christ’s Church not to have been before, but rather that there is no building in the Church but Christ’s work only, for Paul and Apollos be but waterers.”

CHICHESTER: “In good faith I am sorry to see you so light in judging the Church.”

BRADFORD: “My lords, I speak simply what I think, and desire reason to answer my objections. Your affections and sorrows cannot be my rules. If you consider the order and cause of my condemnation, I cannot think but that it shall something move your honours. You know it well enough no matter was laid against me but was gathered upon mine own confession. Because I denied transubstantiation, and the wicked to receive Christ’s body in the Sacrament, therefore I was condemned and excommunicated, but not of the Church, although the pillars of the Church did it.”

CHICHESTER: “No; I heard say the cause of your imprisonment was for that you exhorted the people to take the sword in one hand and the mattock in the other.”

BRADFORD: “I never meant any such thing, nor spake anything in that sort.”

YORK: “Yea, and you behaved yourself before the Council at the first that you would defend the religion then; and, therefore, worthily were you prisoned.”

BRADFORD: “Your grace did hear me answer my Lord Chancellor to that point. But put case I had been so stout as they and your grace make it. Were not the laws of the realm on my side then? Wherefore unjustly was I prisoned. Only that which my Lord Chancellor propounded was my confession of Christ’s truth against transubstantiation, and of that which the wicked do receive, as I said.”

YORK: “You deny the presence.”

BRADFORD: “I do not to the faith of the worthy receivers.”

YORK: “What is that other than to say that Christ lieth not on the altar?”

BRADFORD: “My lord, I believe no such presence.”

CHICHESTER: “It seemeth you have not read Chrysostom, for he proveth it.”

BRADFORD: “I do remember Chrysostom saith that Christ lieth upon the altar, as the seraphim with their tongs touch our lips with the coals of the altar in heaven, which is an hyperbolical locution, of which Chrysostom is full.”

YORK: “It is evident that you are too far gone; but let us come to the Church, out of which you are excommunicate.”

To this Bradford nobly replied: “I am not excommunicated out of Christ’s Church, my lord, although they which seem to be in the Church and of the Church have excommunicated me, as the poor blind man was—John 9. I am sure Christ receiveth me. As I think you did well to depart from the Romish Church, so I think you have done wickedly to couple yourselves with it again; for you can never prove that which you call the Mother Church to be Christ’s.”

CHICHESTER: “You were but a child when this matter began. I was a young man, and then, coming from the university, I went with the world; but I tell you, it was always against my conscience.”

BRADFORD: “I was but a child. Howbeit, as I told you, I think you have done evil, for you have come and brought others to that wicked man which sitteth in the temple of God, that is, in the Church; for it cannot be understood of Mahomet, or any out of the Church, but of such as bear rule in the Church.”

YORK: “See how you build your faith upon such places of Scripture as are most obscure, to deceive yourself.”

BRADFORD: “Well, my lord, though I might by fruits judge of you and others, yet will I not utterly exclude you out of the Church; and, if I were in your case, I would not condemn him utterly that is of my faith in the Sacrament, knowing as you know that at least eight hundred years after Christ, as my lord of Durham writeth, it was free to believe or not believe transubstantiation. Will you condemn any man that believeth truly the twelve articles of the faith, although in some points he believe not the definition of that which you call the Church? I doubt not but that he which holdeth firmly the articles of our faith, though in other things he dissent from your definitions, yet he shall be saved.”

“Yea,” said both the bishops, “this is your divinity.”

“No; it is Paul’s,” replied Bradford, nothing daunted by the sternness of his episcopal persecutors, and he added, “who saith that, if they hold the foundation, Christ, though they build upon Him straw and stubble, yet they shall be saved.”

YORK: “How you delight to lean to hard and dark places of the Scriptures!”

CHICHESTER: “I will show how that Luther did excommunicate Zuinglius for this matter.”

The bishop then read a statement from Luther’s writings to support his assertion.

BRADFORD: “My lord, what Luther writeth, as you mind it not, no more do I in this case. My faith is not built on Luther, Zuinglius, or CEcolarnpadius, in this point; and, indeed, I never read any of their works in this matter.”

YORK: “Well, you are out of the communion of the Church, for you would have the communion of it consist in faith.”

BRADFORD: “Communion consisteth, as I said, in faith, and not in exterior ceremonies, as appeareth both by St. Paul, who would have one faith, and by Trenrens to Victor, for the observation of Easter.”

YORK: “You think none are of the Church but such as suffer persecution.”

BRADFORD: “What I think, God knoweth. I pray your grace to judge me by my words; and mark what St. Paul saith—‘All that will live godly in Christ Jesus must suffer persecution.’ Sometimes Christ’s Church hath rest here; but commonly it is not so, and specially towards the end her form will be more unseemly.”

YORK: “Well, Master Bradford, we leese our labour, for ye seek to put away all things which are told you to your good. Your Church no man can know. I pray you, whereby can we know it?”

BRADFORD: “Chrysostom says, ‘by the Scriptures’ and thus he often saith.”

YORK: “That of Chrysostom in ‘Opere irnperfecto’ may be doubted of. The thing whereby the Church may be known best is the succession of bishops.”

BRADFORD: “No, my lord. Lyra full well writeth upon Matthew that ‘the Church consisteth not in men, by reason either of secular or temporal power, but in men endued with true knowledge, and confession of faith, and of verity.’ Hilary, writing to Auxentius, says that ‘the Church was hidden rather in caves, than did glister and shine in thrones of preeminence.'”

This conference, to which we have somewhat lengthily alluded, was abruptly brought to a conclusion by the arrival of a messenger, informing the two prelates that the Bishop of Durham wished to see them on urgent business; so they bade adieu to Bradford, wishing him well, and hoping their visit would be productive of good results. But the brave martyr was enabled to resist their machinations. Scarcely a day passed during his long confinement without a visit from some bishop, friar, or other person. All these various parties had one object in view. They wished Bradford to desert the ranks of Christ and join their side; but, thanks be unto God, their wishes were never realized.

During his imprisonment, however, there were times of repose. John Bradford was permitted to spend some of his hours in solitude, and these periods he profitably employed in prayer, study, and writing. His letters, remarkable for their elegance of style, simplicity of language, and enunciation of Christian experience, were penned during the period when he was left alone in his cell, unmolested by his enemies. These letters attracted considerable attention, and were subjected to keen criticism in the Houses of Parliament. The Earl of Derby stated, on one occasion, that they had greatly contributed to the spread of “heresy” in the kingdom.

At length Bradford’s imprisonment came to a close. On the day before his execution, he was conveyed during the night from the Compter to Newgate. On the following morning Bradford was conducted to Smithfield, where the stake was erected at which he was to be burned. A companion joined him in the flames. John Leaf, who had been an apprentice in London, suffered at the same stake. On their arrival at the stake, around which a large concourse of spectators had assembled, the two heroes engaged in silent prayer, until they were rudely disturbed by the sheriff, who said to Bradford, “Arise, and make an end, for the press of the people is great.” They then undressed for the fire. When all was ready, the undaunted martyr, with uplifted eyes and hands towards heaven, impressively exclaimed, “Oh, England, England, repent thee of thy sins! repent thee of thy sins! Beware of idolatry! beware of false Antichrists! Take heed they do not deceive you.” The sheriff commanded Bradford to be quiet, threatening to tie his hands unless he was obedient. “Oh, Master Sheriff,” said Bradford, “I am quiet. God forgive you this, Master Sheriff.” One of the officers then said to him, “If you have no better learning than that, you are but a fool, and had best hold your peace.” With the wood crackling and the flames fiercely glaring around him, the happy and peaceful martyr, now on the threshold of everlasting joy and glory, exclaimed, “Strait is the gate, and narrow is the way, that leadeth to eternal salvation, and few there be that find it.” A few moments more, and he was gone! Thus bravely died John Bradford, one of the most noble of England’s “noble army of martyrs!”

With Popery coming in upon us like a mighty flood—with convents, monasteries, and mass-houses constantly creeping up around us—with friars, monks, nuns, priests, and Jesuits busily and craftily at work on every hand—how solemn and how timely does the dying appeal of Bradford sound in our ears: “Oh, England, repent thee of thy sins! Beware of idolatry! beware of false Antichrists!” These words might have been uttered today instead of three hundred years ago. Idolatry of various types is assuming large proportions in our land, and false Antichrists are deceiving vast numbers of our countrymen. Rome is again aiming at supremacy, and her efforts have been crowned with no little success. But thanks be unto God, although that system may imagine that she is on the road to success, yet the day will assuredly come when all systems of error, Rome included, will be dashed into pieces, and truth will reign “o’er the world, supreme and alone.”

John Bradford (1510-1555) was an English Reformer. He served as prebendary of St Paul’s and was the author of several books. Having been accused of crimes against Queen Mary I, he was imprisoned in the Tower of London and burned at the stake in 1555.

John Bradford on the Law and the Gospel (Complete)