Different Shades Of Calvinism

Preface

This article was written for the Earthen Vessel in the year 1909, the author unknown. However, there is a reference at the end which leads me to believe William Styles was the writer. His views, generally speaking, were representative of the Strict and Particular Baptist denomination at the time. Of course, this included not only the churches in association with the Metropolitan Association of Strict Baptist Churches and the Strict Baptist Mission, but many other churches and believers in subscription to the Earthen Vessel. These churches and organizations were Hyper-Calvinists by creed and conviction. Styles uses, for the basis of his article, two recently published works on the life and writings of John Calvin, by William Wileman. Published by R. Banks & Son; and R. H. Irwin, M.A. Published by the Religious Tract Society. After giving a short biographical sketch of Calvin, Styles goes on to distinguish between the different sub-systems of Calvinism, highlighting for instance, the modifications made by Richard Baxter. The reader should be aware, the modifications of Baxter were staunchly opposed by the Particular Baptists of the 17th century, and in fact, was one of the reasons Benjamin Keach rejected the covenantal framework of the 1689 Confession. In his “Everlasting Covenant”, published 1693, Keach writes:

“Question, Is not that Covenant which was made between the Father and the Son (considered as the latter, is Mediator) called the Covenant of Redemption, made from all Eternity a distinct Covenant from the Covenant of Grace? Answer. I Answer…I must confess, I have formerly been inclined to believe the Covenant, or Holy Compact between the Father and the Son, was distinct from the Covenant of Grace; but upon farther search, by means of some great Errors sprang up among us, arising (as I conceive) from that Notion, I cannot see that they are Two distinct Covenants, but both one and the same glorious Covenant of Grace.”

Keach came to the conclusion that the conditional and partial Covenant of Grace propounded by the 1689 Confession was the “means of some great errors sprang up among us,” which were no other than those advanced by Richard Baxter. Henceforth, by embracing the Covenant of Redemption as the only saving agreement upon which sinners are brought into relationship with God, the pernicious teachings of Baxter were uprooted at the source. It was this reform to covenant theology which became the foundation and backbone for 18th century Hyper-Calvinism, a framework of teachings which have dominated the Strict and Particular Baptist churches for the last three hundred years. And interestingly enough, while Keach and his peers combated the false teachings of Baxter at the turn of the 18th century, it was Gadsby and his peers who combated the false teachings of Andrew Fuller at the turn of the 19th century. John Gill stood between these controversies, supporting the views of Keach and Gadsby, by writing a Systematic Theology that has become the quintessential statement on 18th century Hyper-Calvinism. If these men were alive today, they would be writing against the teachings of the Reformed Baptists, who subscribe to the covenantalism of the 1689 Confession and have imbibed various modifications of Baxterism and Fullerism.

Sadly, the Metropolitan Association of Strict Baptist Churches and the Strict Baptist Mission were taken over by the Reformed Baptists during the 1960s, at which time they denounced the tenets of Hyper-Calvinism, remaking the churches in their own image. The transformation was complete when the names of these organizations were changed to “Grace Baptists”. Their opposition to John Gill and the Particular Baptists they claim to represent only accentuates the fundamental differences between the historic Particular Baptists and the Reformed Baptist movement.

I now submit to the reader Styles’ article on Calvin and Calvinism.

Jared Smith

Calvin And Calvinism

A Biographical Sketch

A correct estimate of Calvin’s career is hard to form. He lived and laboured in a remote age. The names of wholly unfamiliar persons and places abound in his life story. Hence, many readers grow embarrassed and abandon the attempt to ascertain the facts of his life.

The commemoration of the fourth centenary of his birth is impending, and interest in this wonderful man will be revived. Two excellent Biographies have recently appeared, and to give in brief what these so fully relate is our object in these papers.

[Many popular sketches of his life in Biographical Dictionaries, etc., are unreliable. “Harmsworth’s Encyclopredia,” for instance, says: “In 1540 he attended the Diet of Worms.” This, as a matter of fact, took place in 1521, when Calvin was but 12 years old.—Editor.]He was born in 1509, of devout Roman Catholic parents, in Picardy, a province of France. Protestantism was then little known, and Popery was all but universal in Europe.

It was at first intended that he should be a cure, or clergyman, to prepare for which vocation he went to a college in Paris, in 1528, and he was made a sort of boy-priest, without, of course, authority to perform the more solemn functions of this office.

In 1528, he changed his purpose, and, to please his father, commenced the study of civil law in the then famous Universities of Orleans and Bonrges. He there added Hebrew to his already extensive attainments.

His attention—through the mercy of God—was at this time (1530) directed to the teachings of Luther. His conversion to God followed, and he became not only a sincere Christian, but a bold champion of the faith of the Reformers and an avowed opponent of the errors of Rome.

In 1531 his father died, which again altered his plans, and he determined to make literature his profession. He returned to Paris where, in 1532, he published his first work, Notes on the “De Clementia” (Concerning Clemency) of Seneca, which, though ostensibly a commentary on a book by a heathen author, was really an oblique plea for mutual toleration on religious questions.

This able and scholarly production commanded the admiration of learned men, but as its principles were directly opposed to those of the cruel and persecuting Church of Rome, it proved obnoxious to the ecclesiastical authorities, who determined on his destruction. His life being thus imperilled, he now became a homeless fugitive, fleeing from place to place to avoid the vigilance of those who sought his death. This was to him a season of gravest trial and peril, which entitles him to rank among those who, in their day, “wandered in deserts, and in mountains, and in dens and caves of the earth; being destitute, afflicted, tormented” (Heb. 11:37, 38).

In 1536 he found a home in Basel, now called Bale or Basle, a town in the north-west of Switzerland, in which Protestantism already exerted great influence. Here the half-hearted Erasmus had lived and, quite recently, died. Here Calvin published the first edition of his great work, “The Institutes (or leading principles) of the Christian Religion,” in which he aimed to state clearly and concisely the essential truths of the faith of Christ.

Leaving Basle in July, 1536, he designed to reside in Strassburg, whither he was proceeding when he was compelled to take Geneva on his way, though intending to sojourn there for one night only.

The Lord, however, had purposed otherwise. Here the Reformation had already taken such hold of the people that, in 1535, they had, as a body, renounced the Church of Rome as Anti-christian and formally adopted Protestantism. They were now longing for further and fuller evangelical teaching, and begged Calvin to stay and favour them with his public and private instructions.

This was not, however, laid on his heart till his friend, William Farel, one of the pioneers of the Reformation who had introduced the pure Gospel to them, persuaded him to continue the good work so auspiciously begun.

In the two years which followed, Calvin not only taught them, as they desired, but published a “Confession of Faith,” a “Catechism,” and the “Articles of the Religion” which they had professed.

But, in April, 1538, a melancholy change occurred. This partly arose through an unhappy discussion whether leavened or unleavened bread should be used at the Holy Communion. But its main instigators were some licentious professors who were incensed at the holiness of his teaching, and his refusal to receive immoral persons at the Lord’s Supper. Public opinion now turned bitterly against both him and Farel, who were compelled to leave the city.

In August, 1538, Calvin again decided to visit Strassburg. Here he was cordially welcomed and appointed the minister of a French Protestant Church, and likewise public lecturer on Divinity—a high and honourable post, which he retained until 1541—at a modest and insufficient salary.

Here, at the age of thirty-one, he married; his wife proving a true helpmeet, though their union lasted but nine years.

The period which followed was occupied with the work which he had undertaken for God, and his Christian zeal and affection, combined with his unselfish and holy life, rendered him the object of universal esteem and love.

In 1541 an event occurred which largely augmented his reputation as a champion of the Gospel of God. At Ratisbon, a Diet or conference of ecclesiastics was summoned to discuss the points of difference between the Roman Catholic and the Protestant religions. This Calvin attended, and distinguished himself by his bold protests against the error of transubstantiation, or that in the Lord’s Supper the bread and wine are by priestly consecration changed into the actual body and blood of Christ. Both the Roman Catholic and the Protestant Divines who were present desired to be conciliatory, but on this—the doctrine of the “real Presence’’—neither could yield, and the convention led to no results.

Luther and Calvin never met, though their mutual esteem was great and they frequently corresponded.

With Philip Melancthon—Luther’s closest friend—he, however, at this time became acquainted, and they henceforth lived on terms of endeared intimacy.

Happy and useful as he now was, this was not to be the scene of his final and most extensive labours. After three years he received a communication from Geneva, expressing regret for his expulsion and begging him return and resume his work for God. This accorded with his own feelings, as his affection for the people of that city was unabated. His friends at Strassburg parted from him with reluctance, giving him most practical assurance of their loyalty and love.

In September, 1541, he was enthusiastically welcomed back by those who had ignominiously banished him; and for the twenty years following his authority and sway were almost unbounded.

He first settled a form of municipal and ecclesiastical government, by the appointment of what was styled “the Consistory’’—a number of godly men chosen to supervise all matters of religion, morals, and education—somewhat resembling the governing body at Massachusetts in the days of the Pilgrim Fathers a hundred years later. The idea was admirable; but since the best of men are men at best, and irresponsible power too often merges into tyranny, their actions were at times far from commendable.

From this time to his death Calvin exerted a far-reaching influence. At Geneva he was almost an uncrowned king. In Switzerland, Holland, France and Scotland, he was regarded as the head of the Reformed Churches; though in Germany, where the sentiments of Luther—from whom he differed on some points—prevailed, his authority was less recognised.

At this period he became acquainted with two illustrious men, John Knox (1505-1572) and Theodore Beza (1519-1605). In 1553 to 1559 the Scottish Reformer repaired to Geneva to escape the persecution of “bloody Mary”; and the two became firmly attached to each other. Beza, a staunch Reformer and the greatest Greek scholar of his day, [His translation of the New Testament into Latin is still of high repute. It is the one issued very cheaply by “The British and Foreign Bible Society.” Its title is “Jesu Christi Domini Nostri Novum Testameutum, Ex intorprctationo Theodori Beze.”] also at one time resided in Calvin’s city, and became his fast friend, and subsequently his successor and biographer.

In 1553 his name was associated with Michael Servetus, a physician and scientist of undoubted ability, who had advocated pantheism, and denied the doctrine of the Trinity in irreverent and even blasphemous terms. For this Rome had—in his absence—condemned him to die at the stake. He therefore sought refuge in Geneva. Though not under the jurisdiction of the consistory, they ordered his apprehension, and, after a long trial, pronounced on him the same sentence as Rome had done, deeming death by slow burning the just reward of his heresy.

The conduct of Calvin in this matter is conceived by many to cast a blot on his otherwise irreproachable character. He could, it is submitted, have insisted that the unhappy man’s life should be spared. He, however, contented himself with pleading that a less cruel way of putting him to death should be adopted. Hence it is urged that his religion could have been worth little—whatever his theological knowledge—if it did not teach him mercy.

On the other hand, the spirit of the age and the current opinions of holy men are advanced in Calvin’s excuse. We are told that both Beza and Melancthon commended this action, the latter issuing a booklet, ‘’De hereticis a Civili Magistratu Puniendis,” On the obligation of a civil magistrate to punish heretics, in which the death of Servetus is justified. These are facts which readers must estimate for themselves.

The many scandalous stories invented by Jesuit historians are unworthy of attention. Others are said to have arisen from the irregularities of a contemporary who also bore the name of Jean Chauvin, but with whom he had no connection. That Calvin was a gracious and good man is unquestionable. He died comparatively young, though the work he accomplished was immense. Beside his civil and ministerial duties, he found time to produce the contents of fifty-nine volumes.

He was a chronic invalid and often suffered acutely, till on May 24th, 1564, he responded to the home-call, and committed his ”brave heroic soul” to his Heavenly Father.

Calvinism As A Theological System

It is currently believed that this famous man was emotionless, hard, vindictive, and devoid of many of the characteristics which render a child of God loving and beloved. A perusal of the two recent Biographies to which the attention of our readers has recently been directed [William Wileman. Published by R. Banks & Son; and by R. H. Irwin, M.A. Published by the Religious Tract Society] will, however, dispel this misapprehension, and convince them that when due allowance has been made for the spirit of his age, and the influences which affected his conduct, he was as good as he was great—an imperial man who should be remembered with the utmost respect.

This conceded, it remains to consider the system of theology which bears his name.

It is commonly believed that a word or term is a satisfactory expression of the thought for which it stands. Thus, few would question the assertion that “everybody knows what is meant by Calvinism,” although the term is employed with great latitude of meaning. Tobias Crisp, Dr. Gill, George Whitefield, John Newton, William Cowper, William Huntington, William Romaine, Andrew Fuller, John Stevens, William Gadsby, J. C. Philpot, James Wells, and C. H. Spurgeon were, for instance, all Calvinists. Every one of these gracious men would have yielded his unfeigned assent and consent to the five doctrines or points which Mr. Wileman gives as the truths which specially characterise this system of theology—Original Sin—Personal Election—Particular Redemption—Effectual Calling—and Final Perseverance. Yet how these differed on other and most important matters is generally known. The term Calvinist therefore conveys but a vague idea of their convictions and testimony.

It may be well to inquire what is generally understood by this familiar word.

Many conceive it to designate a system of Divinity in which all other evangelical truths are subordinated to Election—or God’s eternal choice of a few of Adam’s race to salvation, and His pitiless exclusion of the rest from all participation in His saving mercy.

In fact, to judge from some popular writers, a Calvinist is one whose conception of the Almighty is much that of the vile man who is represented as offering the terrible burlesque of a prayer in a poem by poor Robert Burns:—

“O, Thou who in the heavens dost dwell,

Who, as it pleases best Thysel (Thyself)

Sends one to heaven and ten to hell, all for Thy glory,

And not for any good or ill they’ve done afore Thee.”

What the views of a gracious Calvinist are may, however, be learned from Mr. Wileman’s pages, especially from what he advances on the doctrine of election (page 78).

With this we would associate some of Mr. Irwin’s remarks. “Many,” he says, “if asked ‘What is the distinctive teaching of Calvin?’ would answer, The doctrine of predestination. Yet this occupies a comparatively small place in his teaching. In the English translation of the Institutes we find that this subject occupies four chapters out of eighty-one twenty-fourth part of the whole—and its position is not one of prominence, but of subordination. It come at the close of the third book of the Institutes, in which it follows his teaching on the work of the Holy Spirit, faith, repentance, the Christian life, justification by faith and prayer—including his beautiful exposition of the Lord’s prayer.”

Calvinism, as held by Calvin himself, was, we believe, what is often now styled “the evangelical system.” He gave equal prominence to the will of the Father, the worth of the Son, and the work of the Holy Ghost. Salvation, in his writings, is attributed to purpose, purchase, and power—to mercy, merit, and might; nor is the sovereign love displayed in eternal Election suffered to obscure EITHER the glory of redemption, or the grace which regenerates God’s people and thus originates religion in their hearts.

In the “Chain of Golden Truths” which forms Mr. Wileman’s very valuable ninth chapter, and in which the views of Calvin, as expressed in his Institutes, are epitomised, so far from there being anything extravagant, there is hardly a sentence which might not be uttered by a gracious clergyman or dissenting minister in the present day.

We have already expressed our disappointment that neither of our authors is explicit as to what were Calvin’s published sentiments on the ancient purposes of God in relation to those who die unsaved. Mr. Irwin, indeed, states that “Calvin’s view of reprobation—or election to damnation—is now held by very few” (page 179). What this view precisely was he does not, however, say, nor does he justify his characterising it as “election to damnation”—a phrase which strikes us as very appalling.

Mr. Wileman also informs us (page 78) that by “Reprobation, properly understood,” is meant “the decree of God which justly leaves some persons where their sin has placed them,” in proof of which he cites the Westminster Confession, Chapter III. 7. Reprobation, he states, it is usual to attach with the doctrine of Election, but he likewise refrains from stating what Calvin himself wrote on the subject. Especially we should like to be informed whether he believed in the election or reprobation of such children as die in infancy.

These things, we think, readers of books expressly recounting the “work” and the “teaching” of the Reformer have a right to expect.

We proceed to notice the term Calvinist as used in current religious literature.

The Calvinism Of The Church Of England

For this Toplady ably contended. An examination of the Prayer-book, however, shows it to be of a very heterogeneous character. Election and predestination are, for example, emphatically taught in Article XVII. Elsewhere the Lord is besought to make His “chosen people joyful.” Children are instructed that the Holy Ghost sanctifies “all the elect people of God.” In the Office for the Burial of the Dead God is entreated “shortly to accomplish the number of His elect, and to hasten His kingdom.” In another place Christ is appealed to to spare the people whom He has “redeemed with His precious blood,” and to “be not angry with them for over.” Yet elsewhere the Father is adored because of “His tender mercy, He gave His only Son, Jesus Christ, to suffer death upon the cross for our redemption; Who made there (by His one oblation of Himself once offered) a full, perfect, and sufficient sacrifice, oblation, and satisfaction for the sins of the whole world. Further, in the Litany, “God, the Son,” is addressed as the “Redeemer of the world” and as “the Lamb of God who taketh away ‘—not, as in John 1:29, “the sin,” but “the sins of the world.” How contradictory these statements are need not be insisted on.

The Calvinism Of The Westminster Assembly

That the Confession of Faith and the Longer and the Shorter Catechism are Calvinistic all know; and many for this reason hate them, and desire their total disuse and consignment to oblivion. Yet while asserting in the strongest terms that human salvation depends wholly on the sovereign pleasure of God, it is also taught that the Gospel of Jesus Christ is a Divine tender or proffer of the Saviour to sinners, and that “the Holy Ghost doth persuade and enable us to embrace Jesus Christ freely offered to us in the Gospel” (The Shorter Catechism, Question 31).

Offered and effectual grace—a Saviour who presents Himself for acceptance or rejection, and One who saves with Divine and irresistible energy all that were of old given Him by covenant—are, it need hardly be said, so inconsistent as items of belief that both cannot possibly be true. If salvation is contingent on the will of man, it assuredly does not depend on the sovereign will of God, who consults none but Himself in all His proceedings. Such a display of grace were no grace.

[Not only is the free offer set forth in the Westminster Standards, but also the doctrine of duty faith. The same is true of the 1689 Confession. Editor, J. S.]This is not written in depreciation of these venerable and excellent formularies of the doctrines of true religion, but to point out that while they contain much sterling gospel, they embody a form of error against which men of truth like J. J. West, W. Parks, John Stevens, J. C. Philpot, James Wells, John Foreman, and William Palmer never wearied of protesting, as itself unscriptural and God-dishonouring, and inevitably leading to others of a far more dangerous character.

The Calvinism Of Richard Baxter (1615-1691)

This holy man attempted to unite Arminianism with Calvinism, contending that both alike are scriptural. “He professed,” says William Palmer, “with the Calvinists to believe in election, human depravity, irresistible grace and final perseverance; while with the Arminians he contended for general redemption, initial grace, offers of grace, improvements of grace and falling from grace; but these in relation only to the unchosen part of mankind.” In fact, his curiously amalgamated system seemed to embody the view of a living Baptist minister who was once one of ourselves, which appears to be “the certain salvation of the elect and the possible salvation of the rest of mankind.”

Hence a distinction was made between the “covenanted mercy” which made salvation certain to all the chosen of God, and His “uncovenanted mercies” on the ground of which a vague and uncertain hope was entertained for the salvation of other sinners. “We must leave such an one ‘to the uncovenanted mercy of God”’ was at one time, especially in Scotland, no uncommon expression.

This was supposed to afford ground for the indiscriminate proclamation of the gospel to all men, and earnest and pitiful entreaties to believe it and be saved.

Contradictory as this system—or rather this theology without system—undoubtedly is, it greatly affected the views of other Puritan divines whose works are largely tinctured with it.

At the present day the sermons of many who aim at the conversion of men or at “winning souls” according to the popular phrase, is of this character. Christians, as such, are fed with the rich and enriching doctrines of grace; but in addressing the ungodly the wildest Arminianism is enforced. The saints are bidden to trace all they are and have and hope for to the riches of Divine love, while sinners are assured that they may, can, and should decide for Christ, and without delay accept His offers of mercy.

When reminded of the indubitable fact that truth is evermore consistent with itself, and that both “yea” and “nay” cannot both be the right reply to the same question, they retort, with a recently deceased minister, that both free grace and man’s so-called responsibility are to be found in the Bible, in which the discrepancy complained of originates.

Thus Baxter, though long since with his Lord, still exercises a mysterious influence over brethren whom, we shrink not from saying, we can but love and esteem.

The Calvinism Of Tobias Crisp (1600-1642)

Tobias Crisp was of a respectable and opulent family. After studying successively at Cambridge and Oxford he became Rector of Brinkworth, in Wiltshire, where he was highly esteemed both for his ministry and the sanctity of his life. He at first was an Arminian, but his views changing, he became—in the order of time—the first preacher of Divine grace in its absolute sovereignty and freeness in our country. He retained his charge until his fortieth year, when the disturbed state of affairs in England necessitated his retiring to London, where he died of the small-pox in 1642.

That he is justly entitled to be called a pioneer appears from a glance at the dates of a few of his better-known Puritan contemporaries—Milton (1608-1674), Thomas Goodwin (1600-1679), Baxter (1615-1691), Joseph Alleine (1623-1688), John Owen (1616-1683), John Howe (1630-1705), and John Bunyan (1628-1688).

He is now remembered solely as the author of fifty-two sermons which were afterwards issued in two volumes in 1755, with explanatory notes by John Gill, D.D. These received extraordinary opposition from semi-Pelagian writers, the best known of whom was Daniel Williams, D.D., who, in 1692, published an elaborate refutation of what he judged to be their errors.

[That Dr. Williams (1643-1716) was a truly holy man, and held and taught much evangelical truth, is generally admitted. He, however, held the strange theory that God in grace has receded from the claims of the moral law, and given up its original obligations, and that the Gospel is a new law, but of milder requirements, in which faith, repentance, and sincere but imperfect obedience are substituted in the room of the perfect and perpetual obedience required by the original law. Much of the Gospel of the present day so closely resembles this as to be almost identical with it. It is not, however, prominently advanced in his reply to Crisp’s Christ Alone Exalted. He was the founder of the theological library in Gordon Square, for the maintenance of which, and other purposes, he left £50,000, and his memory is therefore entitled to the respect of all godly persons. All metropolitan pastors should avail themselves of this invaluable institution.]On examination, however, these “errors,” with few exceptions, prove to be truths beloved of all to whom Christ is vitally precious, though at times expressed with a crudeness into which all extemporaneous preachers are liable to be betrayed. The sermons were originally transcribed by the preacher’s son, who at that time must have been a mere boy. They appear to have undergone no revision. As they were delivered warm from a holy and eager heart, so they were given to the world, and therefore claimed an indulgent reception, which was unfortunately denied them.

A thoughtful and prayerful reader will probably be surprised to find that the great doctor’s so-called enormities are, in the main, the very doctrines which he hears from the lips of his pastor—if, indeed, he is favoured to sit under a faithful ministry—every Sabbath of his life.

The “head and front of” this ancient preacher’s “offending” seems to be that he insisted that a heaven-born faith is the fruit and not the cause of union with Christ; that covenant relationship is coeval with the love of God to His people, and not to be dated from the time when they first believe to the saving of the soul; that the graces and virtues of Christians have in themselves no merit, and that any reliance on the goodness of a pious life is derogatory to the glory of Him through whose obedience and oblation blessings unnumbered are freely bestowed upon the elect of God; that the sins of the elect were, in very deed, in a mysterious and inexplicable, but most real way, transferred to Christ, who bore them “in His own body on the tree”; that Jesus does not become our Saviour if we look unto Him by faith, but that He was of old given by covenant to His chosen people to open their blind eyes, and thus to empower them to regard Him as their Saviour; and that sinners are not saved for believing, but that saved sinners are brought to believe that they were of old the objects of His atoning blood, and so to trust Him with the living confidence of personal faith. These, and many other statements of the truth of which all God-taught readers of this magazine are steadfastly persuaded, rang from the lips of this young country clergyman two hundred and seventy years ago.

In one important particular we admit that we cannot follow his teachings. The Gospel declares that “all the sins of all the elect “were made to meet on Christ, who, by His death, made full satisfaction to God for them, and thus eternally effaced them from His judicial recollection, so that He remembers them no more. Hence the objects of His atoning work are exempt from condemnation and freed from the curse of the law, and can never be judicially punished for their sins. As Toplady sings:—

“Payment God cannot twice demand—

First at my bleeding Surety’s hand

And then again at mine.”

None of the afflictions which the saints are called to endure are therefore expressions of the wrath of God.

On this our author insists with the utmost clearness and decision, but, as we judge, he is misleading in inferring from this that God does not chasten His people, and insisting that if He afflicts them it is from sin and not for sin. His error lies in his failing to distinguish between God in His judicial and in His paternal character; His inflicting penal evil on those for whom Christ did not die; and His expressing His holy displeasure as a Father when His heaven-born children disobey Him. [See the reply to the question, “Does God punish His people for their sins?” in Answers to Inquiries, by J. C. Philpot, M.A., in which this subject is ably treated.]

This we deem the main, if not the sole, item of the system of Tobias Crisp which calls for refutation.

His sermons are a wonderful unfolding of Calvinism denuded of the inconsistencies to be found in the writings of the Reformer himself, though the marvel is not that some of his teachings lack the support of Scripture, but that he knew and taught so much truth.

Crisp’s style is clear; his language plain and homely; and his reasoning scriptural and convincing; contrasting strangely with the cumbrous and pedantic writings of the Puritans who succeeded him. His complete works—with the instructive and judicious notes of Dr. Gill—cannot be too highly commended to preachers, and could we but revive a gracious interest in them, and induce our younger brethren to “chew and digest them,” to employ Lord Bacon’s celebrated expression, great would be our joy.

The Calvinism Of Joseph Hussey (1660-1729)

This most able, if somewhat peculiar, divine is mainly known by his two works, The Glory of Christ Unveil’d and God’s Operations of Grace but no Offers of Grace. The first, though ostensibly a refutation of the errors of a feeble book by John Hunt, a minister at Northampton, is really an exhaustive treatise on salvation by free and sovereign grace through the Redeemer’s finished work. Its design and execution are alike eccentric, but its merit is great as an exposition and defence of the true doctrines of the Gospel. The late revered John Hazelton and his friend and contemporary, John Slate Anderson, declared that its perusal affected their whole subsequent ministry for good.

The second book mentioned above is, as its title indicates, designed to refute the error in the Westminster Assembly’s Confession of Faith and Catechisms [together with that of the 1689 Confession, Editor, J. S.]—that the proclamation and presentation of the Gospel consists in proffering, tendering, or offering Christ and salvation for the acceptance of all that hear it. This popular error is dealt with in a masterly way and the nature of the work of the Spirit in the hearts of chosen and blood-bought sinners clearly unfolded.

Hussey had thoughtfully perused the works of many of the Puritans and made what they taught his own. His profiting accordingly appears in his writings, which afford a marvellous display of Calvinism when discussed with high spiritual intelligence and fulness of Scriptural knowledge. The reader who will bear with his oddities and master his ideas, will assuredly find that he is a most bold and original thinker and a suggestive teacher who possesses unwonted power to stir and stimulate thought in others.

Hussey’s books were a distinct advance on any that had preceded them. Thus the Holy Spirit progressively gave light through holy men of God to His Church in England. [These are the reforms that were coming about among the Particular Baptists during the early part of the 18th century—reforms that are rejected, ironically, by those who go by the name of “Reformed Baptists”, Editor, J. S.]

The Calvinism Of John Gill, D. D., (1697-1771)

[Before us is a copy of the first volume of the first edition of the sermons revised and issued by Dr. Gill in 1755. On the fly-sheet it is stated to have belonged to Toplady, who presented it in August, 1769, to John Holmes, Jun., Ex:on. Subsequently in 1794 it was given to Susanna Woolmer by Shirley Woolmer. Like many books of that time, it was published by subscription, a list of those who undertook to purchase copies being appended. Among these are the Right Hon. the Countess of Huntingdon; the Rev. James Hervey, M. A., Rector of Weston Favel, the author of the Meditations; the Rev. Henry Venn, M. A., then of Queen’s College, Cambridge; the Rev. Mr. Robert Hall, of Arnsby, the father of the great preacher of the same name; the Rev. Mr. Chesterton, of Colnbrook, of whom we recently made mention in our historical notes on the Church of which he was Pastor; and two of his people, Mr. Michael Fowler and Mr. Thomas Rayner, some members of whose family are still connected with the Cause.]Wonderful as was the measure of light vouchsafed to John Calvin and Scriptural as is his theology, in the main, it is universally admitted to have embodied contradictions which greatly interfere with its harmony as a system of Divine truth, and militate against its claims to be wholly based on the Word of God.

“It is an indubitable fact that truth is evermore consistent with itself,” nor can we see how a devout person can plead that the Bible asserts in one place what it denies in another, since its inerrancy would thus be fatally impugned, and its authority as the Word of God for ever invalidated.

This John Gill early perceived and with heaven-born confidence was led to conclude that the Gospel as presented in the Bible must be a harmonious whole, consistent with itself, and free from the alleged contradictions which inevitably cast discredit upon it.

To discover the truth and to formulate it into a harmonious system having the direct support of God’s Word, he accordingly made the business of his life.

To do this was not easy. There are texts which some divines allege teach that God is mutable in His counsels and His affections; that the Lord Jesus obeyed and suffered to effect the salvation of all men, but that His benevolent designs are frustrated by those who reject His offered mercy; that He appeals in the Gospel to sinners to permit Him to save them, while the Spirit strives to induce them to do so; that faith is the credence of the mind based on the reliability of the testimony on which it acts, and that its antithesis, unbelief, will be the ground of the just punishment of obdurate and impenitent sinners; that man in his present state is responsible for determining his future destiny; and that the Gospel is a bona fide offer of mercy on God’s part to sinners.

That these propositions were not fairly deducible from the texts advanced in their support, and that salvation as portrayed in the Bible is the work of God from its inception to its consummation, he had therefore to make clear first to himself and then to others.

This necessitated knowledge of a high order, especially familiarity with the learned languages and acquaintance with the writings of Jewish and early Christian writers on the Bible. These, with marvellous labour, he acquired, and at length was able to affirm that he knew the truth not only by the inner teaching of the Spirit, but also from the testimony of the written Word when judiciously and soundly interpreted on principles which no real scholar could gainsay.

His views are to be learned mainly from three of his many works, The Cause of God and Truth, his Exposition of the Old and New Testament, and his Body of Divinity. The first, which is a refutation of the principal errors of the Arminian writers of his day is still valuable for reference. His great Exposition, a monument of his marvellous patience and persistence, is useful as rescuing the texts which are generally cited in favour of semi-Pelagianism from erroneous interpretations. It is, in this respect, beyond price, though his knowledge of New Testament Greek was hardly on a par with others who succeeded him. The Gnomon Nori Testamenti of his great contemporary, J. A. Bengel (1687-17821, the father of true New Testament criticism, though it was published in his life-time, he does not seem to have read, and much information on the subject, which in the present day is considered essential, he did not possess. We therefore hardly agree with many in their estimate of the value of his Commentary on the New Testament to modern readers.

His Body of Divinity is, however, beyond praise. It was written in his later life and contains the cream of his thoughts and the mature fruits of his marvellous scholarship. Learned but free from pedantry, spiritual but without a trace of sanctimoniousness, and dignified in its stately English yet intelligible and readable, it is unique as the treatise on revealed truth.

The theology of Dr. Gill has been called hyper or extreme Calvinism, though its more accurate designation would be “consistent.” It embodies all the essential principles which Calvin taught, denuded of contradictions and carried to their logical and Scriptural issues. Its substance is expressed in the inspired words: “For by grace are ye saved through faith, and that not of yourselves, it is the gift of God.”

[For certain, Gill denounced the free offer of the gospel and saving faith as a legal duty of the unregenerate. This makes him a historic Hyper-Calvinist. Editor, J. S.]The Duty Faith Controversy

A good cause often suffers more from the adherence of half-hearted friends than from the bitterest opposition of its avowed foes.

Calvinism lives not only because it has the manifest support of the Word of God, but because it corresponds with what goes on in the hearts of all God’s living children. Yet Satan hates it, and it is observable that while he stirs up some to belie and abuse it, he moves more, in a bland and gentle way, while they speak in its favour to plead for great moderation in advocating it. Avoid extremes is their motto. State by all means that salvation is all of grace—that

“‘Tis not for good deeds, good tempers, or frames,

From grace it proceeds, and all is the Lamb’s.”

This must, however, be qualified by telling sinners to begin with God, by closing with Christ, and so themselves commencing the good work which will end in their salvation.

The main error by which these misleading teachers are distinguished is their insisting on spiritual faith as a legal or evangelical duty, demanded of unregenerate men, either by the Law or by the Gospel. Few seem to know or even to care which. “So they wrap it up.”

The error of duty-faith appears to have originated early in the eighteenth century, when it was called “the modern question.” [The error was common during the seventh century, as the 1646 Westminster and the 1689 Baptist confessions make clear, Editor, J. S.] How one gracious man resisted it, it is now our business to tell.

In the historic town of Kimbolton, in Hunts, there resided in the early decades of the eighteenth century a worthy blacksmith and farrier named Lewis Wayman. His reputation was unblemished, and he was highly respected by the then Duke of Manchester.

He was also Pastor of the Independent Church, and as such was widely esteemed for his fidelity as a preacher and his knowledge of the Scriptures. His theology was of the school of Dr. Gill, and he avowed his great obligations to Joseph Hussey.

He is said to have possessed great natural humour, and stories of his droll ways and sayings survive to this day.

The Lord had met him at Rowell (or Rothwell), in Northamptonshire, where he joined the Church under Richard Davis, an evangelical minister of high repute, and the author of a book of hymns once very popular. This good man was followed by a Mr. Morris, who is now known only as having held the error of “duty-faith,” which he advocated in 1737 in a pamphlet entitled A Modem Question Modestly Answered—one of the first of the many controversial publications on the subject.

In it he raised the question “whether God, by His Word, makes it the duty of unconverted sinners who hear the Gospel preached or published, to believe in Christ’’—to which he replied in the affirmative, and devoted the rest of his pages to prove this position.

This pernicious little book fell into Wayman’s hands. He felt deeply grieved that this novel and strange doctrine should be forced upon the people who had heard the truth from the lips of their former Pastor. He therefore published a reply, entitled, “A Further Enquiry After Truth, wherein is shown what Faith is required of Unregenerate Persons, and what the Faith of God’s Elect is, which is a blessing of the Covenant of Grace.”

The way is thus opened for the fair and full discussion of the subject, and it is clearly shown that though it is the unmistakable duty of all men to whom the message of the Gospel comes to give it reverent credence and attention, the faith with which salvation is conjoined is incumbent on heaven-born sinners only.

Wayman’s treatise is brief, and his arguments most pithy and concise, yet as an epitome of the whole controversy it stands unrivalled. Very wonderfully, much that was afterwards advanced by erroneous men is anticipated and met.

His definition of faith is in many respects the most satisfactory that has ever been propounded, and though semi-Pelagians have objected to it, it has never been shown to be faulty. “Faith” he judges to be “a sinner’s trust in the Lord Jesus for salvation on the ground of an inward persuasion.” If this is conceded as Scriptural, the error which makes spiritual faith a duty, and all that this error involves, is effectually controverted.

Wayman’s book was introduced to the writer with high encomiums, in 1873, by his venerated friend John Hazelton, as a work which every truthful minister should make his own, and which to him had proved of incalculable benefit.

The error of duty-faith is by many considered comparatively harmless, but the history of our Churches abundantly shows its mischievous character. Like moths in a woollen garment it eats into the structure and fabric of the Gospel of sovereign grace.

This will further appear in a concluding paper which (D.V.) will deal with the Calvinism of Andrew Fuller, J. H. Hinton, and C. H. Spurgeon.

No term in religious literature—as we have observed—is used with greater latitude of meaning than the word Calvinist, which is applied to theologians of the most varying sentiments.

We have, therefore, drawn attention to some Christians of repute who, though they differed widely from each other, might all with equal justice be named after the great Reformer of Geneva.

The Calvinism Of Andrew Fuller

The author of this system was undoubtedly a good and great man, and it is distressing to hear his sentiments ridiculed and his very name made the subject of a senseless and vulgar pun.

The Particular Baptists of his early days had unhappily sunk into a formal and lethargic condition. They still held to the beautiful and scriptural creed of Dr. Gill, but manifested but little evangelical earnestness and zeal for the truth.

[This assessment of the churches is far too general and sweeping to accurately describe the life and function of all the churches at that time. We doubt not that this may have been true of some churches in the vicinity of Fuller, but it cannot be from thence concluded it was the condition of all the churches nation wide. Indeed, if the churches were in such steep decline at that time, then what accounts for their increase in numbers and influence during the 19th century? And we are speaking here of the Hyper-Calvinist Strict Baptists. Their numbers abounded during the 19th century, Editor, J. S.]This the great soul of Andrew Fuller deplored, but he made the mistake of thinking that an amended theology rather than a revival of grace in the hearts of the members of his Denomination was what was needed.

His Calvinism he stoutly maintained; but with it he enforced the doctrine of duty-faith. [He also revived the covenantalism of the 1689 Confession serving as the basis for his duty-faith teachings, Editor, J. S.]

Some worthy preachers had adopted Baxterianism, but a system which involved so many contradictions he could not favour, and he declined even to read Baxter’s writings. The truth he saw must necessarily be consistent with itself. A logical reason must therefore be assigned for its being the legal duty of men to originate their own salvation.

This he found in what is the foundation of his system—the doctrine of the spirituality of Adam—the federal head of the human race. His reasoning was thus unimpeachable. It is indisputably the duty of natural man to be and to do all that was incumbent on the first man before the Fall, since man’s inability, through his sin, to keep the whole Law involves no diminution of its claim. If, therefore, Adam was a spiritual man and spiritual faith was a duty which he was originally under obligation to perform, all men ought to be spiritual, and it is their duty as creatures to believe with the spiritual faith which ensures salvation.

[This is the spiritual aspect of duty faith, which is rejected by many Moderate-Calvinists today. In turn, they argue while the sinner is unable to exercise saving faith in Christ, yet his inability does not negate his responsibility, thus making a moral case for duty faith. The issue on both counts ultimately revolves around the authority under which the sinner is in relationship to or with God—either a covenant of works or a covenant of grace. Since Fuller embraced the covenantal framework of the 1689 Confession, duty faith may forthwith be argued from a covenantal standpoint, which was ultimately why Benjamin Keach rejected a conditional covenant of grace. Editor, J. S.]John Stevens, however, in his Help for the True Disciples of Immanuel, conclusively shows that the principle of holiness originally conferred on Adam was not essentially the same as that which the elect receive on regeneration. He therefore denies Andrew Fuller’s premises, and so shows the futility of his conclusions.

Fuller at first gloried in his triumph and anticipated much blessing from the spread of his views. Towards the end of his life he, however, thought differently, and expressed sorrow at the lack of truth and spirituality in the sermons of many younger preachers who had adopted his views. Fullerism is always attended with a withering blight whenever introduced into Churches of truth.

John Howard Hinton who subsequently took the controversy up, sought to present a consistent system of theology which should harmonise the responsibility of men to originate their salvation by the exercise of faith, with the sovereignty of God, from which salvation is admitted to flow. He is, however, allowed to have failed; his writings are never quoted. The efforts of his great and logical mind have in this matter effected nothing.

C. H. Spurgeon. It is hard to arrive at what views of truth this dear and distinguished servant of God really held. His Calvinism was of the highest school; yet he insisted that it is the duty of unregenerate men to accept Christ, and constantly bade and begged them to believe as the condition of salvation. The fact that divine sovereignity is contradictory to human responsibility gave him, he alleged, no concern. Asked to reconcile these conflicting doctrines, he declined so to do, on the ground that they never quarrelled. He would affirm and virtually deny what he had just said, in the space of a few minutes. If accused of contradicting himself, he would admit the charge, but urge that he did but preach what the Bible asserted, and that it was no part of his mission to explain what God has left engulfed in mystery.

Spurgeon was no Baxterian. This the writer, one of his early students, can confidently affirm. Nor was he a Fullerite—for Fullerism is an harmonious system, and his sermons abound in contradictions. He was himself, and without a peer, and his memory shines in its own unequalled lustre, but to thoughtful men his exact ideas on the presentation of the Gospel must be inexplicable.

The Calvinism Of The Strict And Particular Baptists

This, as C. H. S. often and with perfect truth observed, is not Calvinism but Ultra-Calvinism, since it is more intense in some directions than anything Calvin ever wrote. There are, indeed, doctrinal statements in his works which would never be tolerated from one of our pulpits.

Speaking for himself and his section of the Church, John Stevens wrote thus in his Help for the True Disciples of Emmanuel. “The author is neither a Calvinist, an Arminian nor a Baxterian; [He might have included Fullerism in this category, for the words occur in his work against Fuller’s tenets, which to this day remains unanswered.] yet he believes many things in common with them all, and claims the liberty of dissenting from them all, where in his apprehension they severally deviate from the straight line of truth.”

Our doctrinal belief does not emanate from a man, and so cannot be called after any illustrious name. We must be content to let it remain an unnamed creed till the Lord returns.

In conclusion, we re-echo the words of our brother, Pastor J. E. Hazelton, in his memorable address on March 10th, 1908. “I would say that I wish that the once-loved phrases, ‘a man of truth ‘ and ‘a cause of truth,’ had not fallen into disuetude among us. It is easy to utter witticisms upon these and similar expressions, but they are substantially scriptural.” Certainly they best define our relation, through distinguishing grace, to what God has recorded in His Word and condescended to teach us “in our souls” by His Spirit.

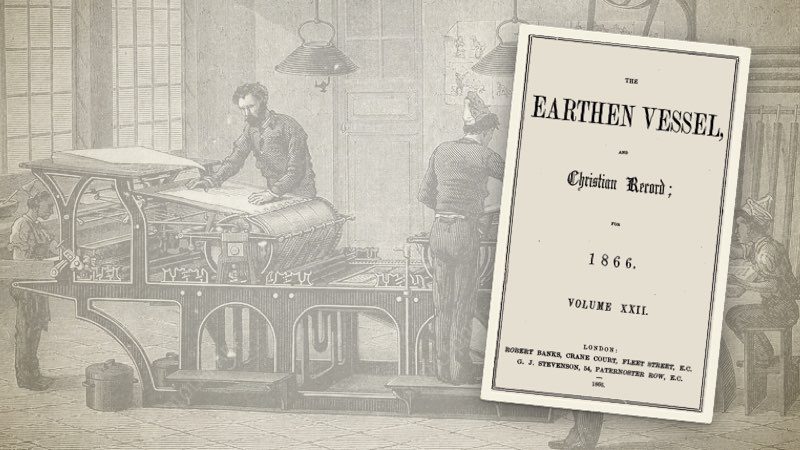

It may be argued the Strict and Particular Baptist churches of the 17th, 18th and early 19th centuries were at their strongest when they remained independent congregations, unaffiliated with Magazines and Societies. This strength was lost during the latter half of the 19th century when the churches clamored around favorite periodicals and regional associations. Although the Magazines were largely responsible for creating a party-spirit and culpable for stirring up needless controversy, they nevertheless contain many valuable resources which may prove a blessing for this generation. Although they differed on various points of doctrine, they invariably held to high views of sovereign grace, denouncing as heresy the pernicious teachings of Andrew Fuller. The majority of Strict and Particular Baptist churches during the 18th and 19th centuries were Hyper-Calvinists.