Andrew Fuller: A Liberal Theologian

Andrew Fuller was a Particular Baptist preacher. He was born in 1754 and died in 1815 at the age of 61. Fuller grew up at a time when John Gill was in the height of his gospel ministry at the Carter Lane Chapel in London. Gill was recognized as the leader of the denomination, if we could describe the Particular Baptists as a denomination at that time. As a prolific writer, Gill published many works, his magnum opus being a Body of Divinity in the year 1769. Fuller would have been fifteen years old when Gill’s systematic theology came off the press. It was in the same year Fuller made a profession of faith. Although he grew up in the circle of churches which embraced Gill’s theological views, he came to despise the teachings. He felt the preaching of his day was dry and disconnected from the man on the street, and said very little to the unconverted about their obligation to believe on Christ. Forthwith, he set upon a study of theology and history, drawing the conclusion that Gill’s teachings were not representative of the theological position of the earlier Particular Baptists. It was on this basis Fuller began to publish materials during the 1780s, while he was in his 30s, which he believed was in accordance with the principles of the Protestant Reformation and the early Particular Baptists.

I will give a couple of examples on how the teachings of Fuller differed from those of Gill.

The first example is taken from 1 Corinthians 7:22,23: “For he that is called in the Lord, being a servant, is the Lord’s freeman: likewise also he that is called, being free, is Christ’s servant. Ye are bought with a price; be not ye the servants of men.” In his commentary on 1 Corinthians, John Gill explains:

“These words are to be read affirmatively, and to be understood of all, whether freemen or servants, that are bought with the inestimable price of Christ’s blood, as in (1 Cor 6:20) and contain in them a reason why such as are called by the grace of God, whilst in a state of civil servitude, are Christ’s freemen, because they are redeemed by him from sin, Satan, the law, and from among men; and also why such as are called by the grace of God, being in a state of civil liberty, are Christ’s servants, because he has purchased them with his blood, and therefore has a right unto them, both to their persons and service:”

Now, Andrew Fuller was not pleased with this type of teaching. He rejected, what he called the Commercial view of the atonement. He said one must not understand redemption to be some kind of payment Christ makes in the atonement. He did not believe sin is a debt, nor did he believe the atonement was the payment of that debt. Rather, he embraced what he called the Governmental view, namely, that by the death of Christ, God displayed His displeasure towards sin, magnifying His justice by the symbol of the cross.

The second example is taken from 2 Corinthians 5:21: ”For he hath made him to be sin for us, who knew no sin; that we might be made the righteousness of God in him.” Again, in his commentary on 2 Corinthians, John Gill explains:

“Christ was made a sacrifice for sin, in order to make expiation and atonement for it; besides all this, he was made sin itself by imputation; the sins of all his people were transferred unto him, laid upon him, and placed to his account; he sustained their persons, and bore their sins; and having them upon him, and being chargeable with, and answerable for them, he was treated by the justice of God as if he had been not only a sinner, but a mass of sin; for to be made sin, is a stronger expression than to be made a sinner: but now that this may appear to be only by imputation, and that none may conclude from hence that he was really and actually a sinner, or in himself so, it is said he was “made sin”; he did not become sin, or a sinner, through any sinful act of his own, but through his Father’s act of imputation, to which he agreed; for it was “he” that made him sin: it was he that “laid”, or “made to meet” on him, the iniquity of us all; it was he that made his soul an offering for sin, and delivered him up into the hands of justice, and to death, and that “for us”, in “our” room and stead, to bear the punishment of sin, and make satisfaction and atonement for it; of which he was capable, and for which he was greatly qualified: for he knew no sin; he never was conscious of any sin to himself; he never knew anything of this kind by, and in himself; nor did he ever commit any. This is mentioned, partly that we may better understand in what sense he was made sin, or a sinner, which could be only by the imputation of the sins of others, since he had no sin of his own; and partly to show that he was a very fit person to bear and take away the sins of men, to become a sacrifice for them, seeing he was the Lamb of God, without spot and blemish; also to make it appear that he died, and was cut off in a judicial way, not for himself, his own sins, but for the transgressions of his people; and to express the strictness of divine justice in not sparing the Son of God himself, though holy and harmless, when he had the sins of others upon him, and had made himself responsible for them. The end of his being made sin, though he himself had none, was, that we might be made the righteousness of God in him; the righteousness of Christ; so called, because it is wrought by Christ, who is God over all, the true God, and eternal life; and because it is approved of by God the Father, accepted of by him, for, and on the behalf of his elect, as a justifying one; it is what he bestows on them, and imputes unto them for their justification; it is a righteousness, and it is the only one which justifies in the sight of God. Just as Christ is made sin, or a sinner, by the imputation of the sins of others to him; so they are made righteousness, or righteous persons, through the imputation of his righteousness to them; and in no other way can the one be made sin, or the other righteousness.”

Once again, Andrew Fuller found error in the teachings of Gill. Fuller rejected the real, actual and proper imputation of sin to Christ and the real, actual and proper imputation of Christ’s righteousness to sinners. Having dichotomized the word imputation, he argued there is a proper or literal meaning of the term, and an improper or figurative meaning. While Gill took the view that Christ properly and literally was made sin and the sinner is properly and literally made the righteousness of Christ, Fuller took the view that Christ improperly or figuratively was made sin and the sinner is improperly or figuratively made the righteousness of Christ. Of course, an improper or figurative imputation of sin and righteousness leaves the sinner with only an improper and figurative justification, and when this is added to Fuller’s denial that sin is a debt and the atonement of Christ is the payment of that debt, the heart of the gospel is ripped out of salvation, leaving the sinner to linger in actual, real, proper and literal sin and under the actual, real, proper and literal wrath and condemnation of God. There is in Fuller’s message no gospel, no good news, no real salvation to deliver the sinner from sin, death, wrath and condemnation.

Henceforth, when I call Andrew Fuller a liberal theologian, which is the title of this study, I do so on good grounds. Fuller denounced orthodox Christianity, but such was the subtlety of his writings, he cloaked his heresy with new definitions and intricate philosophizing, leaving the believer spinning in the wind of his dungheap of doctrinal excretions. Well, for the remainder of this study, I wish to speak about Fuller—his place in history and the influence his teachings continue to have in our generation.

When Fuller examined the theology of Gill, he recognized the great theologian had made several reforms to covenant theology. These reforms included, not only the advancement of a single covenant of salvation between the TriUne Jehovah on behalf of the elect, but also the tenets of what Fuller called Hyper-Calvinism—that saving faith is a gift rather than a moral duty of unregenerate sinners; that the gospel should be preached rather than offered to unregenerate sinners. In an attempt to undo these reforms, Fuller reverted to the covenantal framework set forth in the 1689 Confession, which not only dichotomizes the covenant of salvation, but opens the door to the doctrines of duty faith and the free offer. However, feeling this was not a sufficient ground upon which to advance his duty faith and free offer principles, he set upon a redefinition of the great doctrines of salvation. As a result, the Particular Baptist churches of the 18th century, which until that time was one denomination, split into two distinguishable groups. Fuller himself labelled each division the “Hyper-Calvinists” and the “Strict-Calvinists”. He had another category which he called “Moderate-Calvinists”, described as those churches which embraced Baxterism, but for all practical purposes, the “Strict-Calvinists” came to embrace Baxterian teachings, and therefore the names eventually became interchangeable—a Strict-Calvinist was a Moderate-Calvinist.

The Hyper-Calvinists were also called Gillites, as the preachers and churches subscribed to the reformed views (18th century covenant theology) and orthodox teachings of John Gill. The Strict-Calvinists were called Fullerites, as the preachers and churches embraced the reverted views (17th century covenant theology) and/or the unorthodox teachings of Andrew Fuller. There is widespread misinformation regarding both groups, the first group invariably vilified as heretics and the second glorified as the standard-bearers of truth. As it is believed Hyper-Calvinism kills evangelism and spells the end of church life, Andrew Fuller is held forth as the hero who rescued the Particular Baptist churches from oblivion.

To support this view, it is asserted the Particular Baptists, having “fallen into Hyper-Calvinism” under the teachings of Gill, suffered a state of spiritual and numerical decline during the first three quarters of the 18th century. However, with the death of Gill in 1771 and the publication of Fuller’s “The Gospel Worthy Of All Acceptation” in 1785, the churches were awakened out of their slumber and a revival came to the Particular Baptists. This analysis is supported by Baptist historians such as Joseph Ivimey who published several volumes during the early 19th century on the English Baptists. However, Ivimey took his data on church growth during the mid 18th Century and drew his conclusions from a single source, that of John C. Ryland. Not only were the numbers given by Ryland incomplete, but it was not his purpose to provide a comprehensive listing of all Particular Baptist churches at that time. This did not bother Ivimey. As he was antagonistic to the tenets of Hyper-Calvinism, the low numbers played into his narrative that Hyper-Calvinism kills evangelism, and therefore recorded this propaganda in his “historical” writings. Although Ivimey acknowledged he consulted the Thompson list of churches and a few other references, it is clear from the list the adjustments were minimal. He estimates there were only around 200 churches (maybe less) during the 1750s, although he qualifies the numbers with the important disclaimer—“After all (calculations), I suppose it is defective.” In 2001, Robert Jarvis submitted a Ph. D., paper on this subject, demonstrating a numerical growth of the churches during the 18th century, and therefore dispelling the myth that Hyper-Calvinism was the cause of an existential decline of the churches. According to his research, there were over 400 churches by the year 1773, just two years after Gill’s death, and twelve years before Fuller published his infamous book, meaning the numbers supplied by Ivimey and those which are generally used to decry Hyper-Calvinism, misrepresent the true condition of the churches during the 18th century. The findings of Jarvis are all the more astonishing, as he did not subscribe to the tenets of Hyper-Calvinism and therefore unlike others, was not driven by a prejudicial predisposition against the Gillite churches. Too often, historic data is twisted to fit one’s ideological views.

Nevertheless, it is under the false notion that the Particular Baptists of the 18th century were in decline, that Andrew Fuller is held forth as the savior of the churches. Now, if Fuller confined his teachings to those of the 17th century, epitomized in the major confessional statements of that era, then perhaps he could be credited as some sort of hero, undoing the reforms introduced to covenant theology by Benjamin Keach and developed by John Gill. However, that is not what he did. Rather, he used the covenantal framework of the 17th century as a springboard, introducing several innovations and making numerous modifications to orthodox Christianity. As a result, the teachings of Fuller were to the 18th and 19th century Particular Baptists what the teachings of Richard Baxter were to the 17th century. Both men undercut free grace and denounced fundamental teachings of orthodox Christianity. And the Particular Baptists of both eras, stedfast in their convictions of free grace and orthodoxy, stood against Baxterism and Fullerism.

I wish now to change gears to modern times. With the emergence of the Reformed Baptist movement during the 1950s, generally speaking the churches embraced the covenant theology of the 17th century, encapsulated in the 1689 Confession, maintaining the orthodox views of Christianity. However, from the 1980s onwards, various publishers such as the Banner of Truth, Reformation Today and the Founders Journal began to republish and promote the teachings of Andrew Fuller. Although he had been previously credited with saving the Particular Baptist churches of the 18th century, he was now heralded a great theologian; in fact, the greatest Baptist theologian of all time. There are many historians and theologians today, belonging to the Reformed Baptist movement, who elevate Fuller to the status of a Luther, Calvin or Owen.

Of course, this was also the view of the Prince of Preachers, Charles Spurgeon. In 1831, Andrew (Fuller’s son) oversaw the publication of his father’s writings in five volumes. Incidentally, this was the same year William Rushton published his celebrated book against the teachings of Fuller. In 1882, Andrew published a biography of his father entitled, “Andrew Fuller”. He sent a copy to Spurgeon with this reply of gratitude—“…I have long considered your father to be the greatest theologian of the century…You have added moss to the rose, and removed some of the thorns in the process.” Here we have Spurgeon’s typical word imagery, comparing Fuller to a rose, his son’s biography to the moss adorning the rose and the thorns to the prickly parts of his teachings. Well, if Spurgeon showed more regard for the thorns than the moss, he might have come to a different conclusion. Nevertheless, this testimony demonstrates that even the best of preachers may lack discernment and better judgment on matters.

I suspect Fuller has been given this legendary status, especially during modern times, largely because those who read him do not understand him. For instance, since he frequently redefines commonly used terms, the reader must first figure out what he means by those terms before attempting to understand the various concepts for which he argues. Also, he often approaches the Scriptures by dichotomizing words into literal and figurative meanings. When a text supports his view, he interprets it literally; but when it contradicts his view, he interprets it figuratively. He takes the same approach with various doctrines. One must therefore wade through a maze of new definitions and philosophizing before gaining a proper understanding of his teachings. While the reader may ignore these things and interpret Fuller anyway he/she wishes, the result will be the teachings of the interpreter rather than Fuller.

There appears to be a common misconception, particularly among the Reformed Baptists, that the Moderate-Calvinism of the 17th century, represented by the 1689 Confession, is congruent with the Modified-Calvinism of Andrew Fuller. Indeed, when the writings of Fuller are compared with the 1689 Confession, it is quite evident he denounced many articles of the faith. For instance,

1689 Confession, Article 8: Of Christ The Mediator

Paragraph 4—Fuller rejected the view that Christ was made sin and a curse for His people, enduring most grievous sorrows in His soul, and most painful sufferings in His body, for the redemption of His people.

Paragraph 5—Fuller rejected the view that the Lord Jesus Christ purchased an everlasting inheritance in the Kingdom of Heaven, nor did He believe any such blessing was set aside solely for those whom the Father had given to Him.

Paragraph 6—Fuller rejected the view that the atonement was the payment of sin’s debt, and therefore did not believe Christ paid a price in redemption.

Paragraph 8—Fuller rejected the view that the sufficiency of Christ’s atonement is proportionate with its efficacy.

1689 Confession, Article 11: Justification

Paragraph 1—Fuller rejected the view that the obedience of Christ is imputed for righteousness, setting in its place the act of believing.

Paragraph 3—Fuller rejected the view that Christ (1) by His death discharged the debt of sinners; (2) by the sacrifice of Himself, in the blood of His cross, underwent in their stead, the penalty due unto them; (3) made a proper and real satisfaction to God’s justice in their behalf; (4) that both the exact justice and rich grace of God might be glorified in the justification of sinners.

1689 Confession, Article 17: Of Perseverance Of The Saints

Paragraph 2—Fuller rejected the view that the perseverance of the saints depends upon the efficacy of the merit of Jesus Christ and union with Him.

These points are dealt with at length by William Rushton, whom I will soon introduce. This liberal theology imbibed by Fuller—setting forth the atonement of Christ as a symbol of God’s justice rather than a payment for man’s sin—was the precursor for the dissolution of the Fullerite churches at the end of the 19th century. As stated earlier, there emerged at the beginning of the 19th century two denominations of the Particular Baptists—the Gillites and the Fullerites. The Fullerites, having organized the Baptist Union in 1813, banded together as a denomination under its governance. William Lumpkin, in his “Baptist Confessions Of Faith”, singles out Fuller and his teachings to be the leading cause for the decline of this denomination throughout the 19th century:

“As the leading theologian of his era, Fuller sought to unite the doctrinal strength of Calvinism with the evangelical fervor of the old General Baptists. He did this through his theory of redemption, according to which he separated the doctrine of a general atonement from the doctrine of a particular redemption. Keeping the Calvinistic framework, he added to it the old General Baptist emphasis on a General Atonement. Thus Baptists were prepared to offer the gospel to every creature and to pioneer in the foreign missions enterprise…Little remained to keep Calvinistic and Arminian Baptists apart, and they gradually were drawn together. Common tasks called for united effort. The Baptist Union, formed as early as 1813 as a Particular Baptist (Fullerite) national body, was to be the inclusive organization. In 1887 the Council and Assembly of the Union voted for amalgamation of the two bodies and referred the matter to local associations, who generally replied favorably. In 1891 the New Connexion Association (General Baptists) accepted the invitation of the Union to membership.”

The Fullerite churches, as a Particular Baptist denomination, ceased to exist at the turn of the 20th century, having been amalgamated with Arminian and theological liberalism. Of course, it is the inclusion of Arminianism and theological liberalism that distinguishes the teachings of Fuller by the nomenclature Fullerism. How ironic—while the Reformed Baptists charge Hyper-Calvinists with heresy, pointing the finger at the supposed decline of their churches during the 18th century, they ignore the heresy of Fullerism, overlooking the decline of his churches during the 19th century. In the end, when the Reformed Baptists emerged during the 1950s, the only Particular Baptist denomination remaining was that of the Hyper-Calvinists. Is there not also a little irony in Spurgeon’s testimony (that Fuller was the greatest theologian of the century), when it was at the Metropolitan Tabernacle (which at that time went by a different name and met at a different building) that the Baptist Union was formed in 1813, based on the influences of Fuller; leading to the Downgrade Controversy in 1887; causing the Metropolitan Tabernacle to resign from the Union the same year; and ultimately putting Spurgeon into an early grave in 1892, for by all accounts, it was his fight with the Baptist Union and the decline of the Fullerite churches which broke his heart and body.

A contemporary of Fuller’s was a Hyper-Calvinist Particular Baptist preacher named William Gadsby (1773-1844). Gadsby served as pastor for the churches meeting at Hinckley Chapel, Leicestershire (1794-1805) and Rochdale Road Chapel, Manchester (1805-1844). The tenets of Hyper-Calvinism did not hinder his evangelistic zeal and outreach, for under his gospel labors, he traveled by foot across much of Northern England, organizing more than 40 churches while he served as a full time pastor of a large congregation. He was an advocate of Sunday Schools, believing the gospel should be taught to children early in life. His gospel of free and sovereign grace attracted large crowds to the Sunday services, and the membership of the church increased accordingly. Let it be said, the evangelistic zeal and outreach of Hyper-Calvinist Gadsby far exceeded that of Moderate-Calvinist Fuller. In 1844, John (Gadsby’s son) published a memoir of his father, wherein he records the following anecdote when Gadsby first arrived in Manchester:

“I recollect my first visit to Manchester very well. It is now more than forty years since…I had heard that the Baptist chapel in Manchester was destitute of a minister; that there was no religion preached here but what is called by some high Calvinism, and low Calvinism, the latter being a religion of the mongrel breed (Fullerism). Well, I wrote a letter to Manchester, saying that I understood the Baptists were without a minister, and, as I had some business to do there, if they had no objection, I would supply for them for a week or two…and the answer I got was a very cool request to supply the place for a month. Well, I contrived not to get into Manchester till about eleven o’clock on Saturday night…I met the deacon, who took me to his house, and asked me what I would have for supper. I asked for some gruel, intending to be off to bed as soon as I could. But just as I sat down to eat he said, ‘Pray, Sir, are you a Fullerite, or a high Calvinist?’…I tried to evade an answer at first…[but] he seemed to think, certainly, that I did not understand the question, but he was determined I should. He said, ‘You know there is a division amongst the Baptists don’t you?’ ‘A division!’ I said, affecting surprise. ‘Don’t you know,’ he resumed, ‘that there are some Baptists here that they call Fullerites, and some that are not?’ ‘Well,’ I replied, ‘I think I have heard something about it.’ ‘Well now,’ he said, ‘I should like to know which of the principles you embrace, for there have been some strange persons from your part of the country.’ ‘Sir,’ I answered, ‘let me alone to night, and you shall know all about it before twelve o’clock tomorrow’ (after the preaching). ‘No,’ he said, ‘I must know tonight!’…As he would have an answer, ‘Well,’ I said, ‘I am not a Fullerite!’ The result was better than I expected, for he seemed pleased with my answer; for he said he was afraid I was.”

That the Particular Baptists were divided between two denominations was acknowledged as early as 1805. That the Hyper-Calvinist denomination recognized the heretical views of Fullerism was also acknowledged as early as 1805. In fact, John includes the following footnote at the end of the foregoing anecdote—“Mr. Gadsby always considered, and often stated publicly, that Andrew Fuller was the greatest enemy the church of God ever had, as his sentiments were so much cloaked with the sheep’s clothing.” While many have interpreted Gadsby’s comments to be a reference to the free offers of the gospel espoused by Fuller, the truth is, Gadsby recognized the modifications Fuller was making to the cardinal truths of the Christian faith, and it was for that reason he took a public stand against the heresies of Fuller cloaked with the sheep’s clothing.

The Reformed Baptists would do well to distinguish between the Moderate-Calvinism of the 17th century Particular Baptists and the Modified-Calvinism of Andrew Fuller. While the Particular Baptists of the 17th century shared the same covenantal framework with that of Fuller, they certainly would not have embraced or commended his modifications to orthodox Christianity.

Now, all of this brings me to say something about that book I mentioned earlier in the study—that celebrated book written by William Rushton, the same year (1831) the writings of Fuller were published in five volumes.

William Rushton (1796-1838) was a Hyper-Calvinist Particular Baptist preacher. He was a contemporary with Fuller, but only in his youth. He began his gospel ministry around the time Fuller died. In the year 1830, Rushton was encouraged by a friend to read Fuller’s “Dialogues, Letters, and Essays”. This he did. The year after, he wrote a series of four letters to his friend detailing the heresies he discovered in the writings of Fuller. These letters were published entitled, “A Defense Of Particular Redemption; Wherein The Doctrine Of The Late Mr. Fuller, Relative To The Atonement Of Christ, Is Tried By The Word Of God.”

Because Rushton formatted his comments in a series of letters, the content is not arranged topically or systematically. As a result, the work is unaccessible to the “average” believer. Most Christians do not have the time or the inclination to read through lengthy letters without a clear division of thought. For this reason, I have rearranged Ruston’s letters, placing his teachings under main headings and subheadings. The reader will now be able to read the book in sections, according to the topical divisions, which will no doubt make it far easier to study the heretical views of Fuller. The outline (headings and subheadings) are my own; everything else belongs to Rushton.

I have uploaded the book to The Baptist Particular. Allow me to give you a preview of the table of contents, as it may spark an interest for you to study further the heretical views of Andrew Fuller:

Introduction

1. The Reason For This Publication

2. Half Truths Are More Sinister Than Open Error.

3. A Great Change Has Taken Place Since The Death Of John Gill (1770s-1830s).

4. Andrew Fuller Was The Leader Of The Opposition.

5. The Tenets Of Hyper-Calvinism Were Set Forth By John Rippon In His Report For The “Baptist Annual Register” (1801-02).

6. Very Few Readers Of Andrew Fuller Understand The Convolutions Of His Teachings.

7. The Cardinal Error Of Fullerism Revolves Around The Doctrine Of Christ’s Atonement.

I. Fuller Rejects The Doctrine Of Justification.

II. Fuller Rejects The Actual Imputation Of Sin And Righteousness.

1. Fuller’s Distinction Between The “Proper” And “Improper” Meaning Of Imputation.

2. Fuller’s Distinction Between “Sin” And The “Effects Of Sin” Imputed To Christ.

3. The Many Absurdities To Which Fuller Has Subjected Himself By A Denial Of Sin’s Imputation.

III. Fuller Rejects The Commercial View Of The Atonement—That Sin Is A Debt And Atonement Is The Payment Of That Debt.

1. Fuller Subscribes To Many Heresies Of Socinianism.

(1) The Chief Design Of The Death Of Christ Is To Express God’s Hatred To Sin, Rather Than To Make Atonement For Sin.

(2) All The Virtue Of The Atonement Lies In The Appointment Of God, Rather Than The Purchase Of Christ.

(3) Salvation Is Viewed As A Matter Of Justice, Rather Than The Free Unmerited Mercy Of God In The Pardon Of Sin.

2. Fuller Rejects The View That Sin Is A Debt And The Atonement Is Payment For That Debt.

3. Fuller Rejects The View That The Death Of Christ Was Vicarious.

IV. Fuller Rejects The Commensurate View Of Particular Redemption—That The Sufficiency Of Christ’s Atonement Is In Proportion To Its Efficacy.

1. The Proper Meaning Of Redemption.

2. The Inconsistency Of A Particular Redemption Under The Canopy Of A General Atonement.

3. Particular Application Of The Atonement Agrees Only With Particular Redemption.

4. The Nature Of A Perverted Gospel—“Yea, Yea, And Nay, Nay”.

V. Fuller Rejects The Covenant Union Of Christ And His People.

VI. Fuller Rejects The Death Of Christ As The Procuring Cause Of Saving Faith And Repentance.

VII. Fuller Rejects The Obedience Of Christ As Imputed To The Sinner For Righteousness.

VIII. Beware Of False Prophets—You Shall Know Them By Their Fruits.

1. Insincerity And Hypocrisy Often Attend The Reception And Preaching Of A Perverted Gospel.

2. The Tendency Of A “YEA And Nay” Gospel Produces A Worldly Profession Of Faith.

3. A Perverted Gospel Tends To Scatter The People Of God By Destroying Their Bond Of Union.

4. The Doctrine Of Indefinite Redemption Is Greatly Injurious To The Comforts And Joys Of Believers.

5. The Doctrine Of Indefinite Redemption Cannot Support The Mind In The Solemn Hour Of Death.

Conclusion

And so, you see how easily it is to navigate the teachings of William Rushton if you wish to study these things further.

But before I close, I must not end this teaching without making reference to George Ella’s book, “Law and Gospel in the Theology of Andrew Fuller”. Peter Meney is a High-Calvinist Particular Baptist preacher and editor of the New Focus Magazine. In fact, you can sign up for the quarterly magazine through the website, which I encourage you to do. Peter also manages Go Publications, which seeks to promote “the Christ-centered Gospel of God’s free and sovereign grace.” You may access the selection of books from the main page, where you will find over forty titles covering various topics such as theology, history and biography. On the list you will come across George Ella’s “Law and Gospel in the Theology of Andrew Fuller.” If you are interested to dig deeper into the heresies of Fullerism and discover more details about the history of the Particular Baptists during the 18th and 19th centuries, you will not be disappointed with this volume. The advert reads:

”Andrew Fuller’s theology changed the face of evangelicalism at a time when new lands were opening up to the gospel. Fuller was hailed as a teacher of a new era and his theological mark is evident still in the preaching of our day. What did Andrew Fuller teach and just how valuable has been his legacy to the Christian church? Dr Ella turns his able hand to exposing how one man’s ideas, which pass for evangelical Calvinism have little to do with true Biblical Christianity. Fuller’s widespread and popular system of theology has blown a chill-wind over many ministries and blighted much faithful preaching of free grace. This book will be of great interest to all who long for the recovery of distinctive, christ-centred gospel preaching in our churches today.”

My dear friends, buy the book and read the book! You won’t regret the investment of time and money.

Well, I want to thank you for your time and attentiveness throughout the study. I realize topics of this kind are not the most interesting, nor do they seem very relevant, especially if you are not personally confronted or directly influenced by the teachings of Fullerism. However, one of the reasons the Hyper-Calvinist section of the Particular Baptist churches have fallen away during the 20th century is because preachers did not warn their people of the dangers connected with Fullerism, nor did they inform their people of their rich heritage as Gillite Baptist Churches. There were good reasons the churches subscribed to the tenets of Hyper-Calvinism, and good reasons those churches stood against the errors of Fullerism, and if the Lord’s servants do not stand on the watchtower and guard the castle gates, we must not be surprised if the enemy sneaks in and does his worst to its inhabitants. And I say to you, though you may not be under the direct influence of Fullerism, it is alive and multiplying in our day, and I guarantee you have been more influenced by the heresies than you realize. It may surprise you to know, while the Gospel Standard churches remain the largest section of the historic Gillite chapels today, there are well under a hundred chapels left, and of these, many continue to close due to non-membership and others are leaving the Gospel Standard for the Reformed Baptist movement. And of course, over the last 20-30 years, the Reformed Baptist movement has been adopting many of the heresies propounded by Fuller. May God preserve us from such error, not only as individuals, but as churches to which we belong.

I wish upon you, my dear friends, that blessing, and every blessing in the Lord!

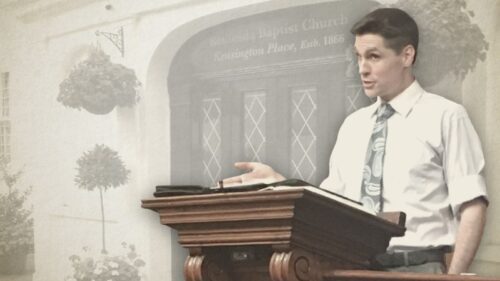

Jared Smith served twenty years as pastor of a Strict and Particular Baptist church in Kensington (London, England). He now serves as an Evangelist in the Philippines, preaching the gospel, organizing churches and training gospel preachers.

Jared Smith's Online Worship Services

Jared Smith's Sermons

Jared Smith on the Gospel Message

Jared Smith on the Biblical Covenants

Jared Smith on 18th Century Covenant Theology (Hyper-Calvinism)

Jared Smith on the Gospel Law

Jared Smith on Bible Doctrine

Jared Smith on Bible Reading

Jared Smith's Hymn Studies

Jared Smith on Eldership

Jared Smith's Studies In Genesis

Jared Smith's Studies in Romans

Jared Smith on Various Issues

Jared Smith, Covenant Baptist Church, Philippines

Jared Smith's Maternal Ancestry (Complete)