What Is A Reformed Baptist?

According to the Founders Ministries, Tom Hicks serves as the Senior Pastor of First Baptist Church of Clinton, LA. He also serves on the board of directors for Covenant Baptist Theological Seminary and is an adjunct professor of historical theology for the Institute of Reformed Baptist Studies. I was recently asked to give a response to his article entitled “What is a Reformed Baptist”. I submit the following, believing it may be of help to others who are examining the differences between the Reformed and Particular Baptists. Tom Hicks writes:

What is it that makes a “Reformed Baptist” distinct from other kinds of Baptists and Reformed folks? Reformed Baptists grew out of the English Reformation, emerging from Independent paedobaptist churches in the 1640’s for some very specific theological reasons, and they held to a particular kind of theology. Here are some of the theological identity markers of Reformed Baptist churches.

This is not true. The Reformed Baptist movement grew out of the Banner of Truth Trust, registered in 1957 as a non-profit charity, spearheaded by Sidney Norton, Iain Murray and Martyn Lloyd-Jones. In 1970, Erroll Hulse founded the Reformation Today magazine. These publications became the organ of a new group identifying as Reformed Baptists. Prior to this time, no Baptist group used this label, nor did any group exist bearing the peculiar earmarks of the Reformed Baptist faith. Although the Reformed Baptists lay claim to the history and heritage of the seventeenth century Particular Baptists (PB’s), they are a twentieth century denomination, quite distinct from the history and teachings of PB’s.

1. The Regulative Principle of Worship. This distinctive is put first because it is one of the main reasons Calvinistic Baptists separated from the Independent paedobaptists. The Particular (or Reformed) Baptists come from Puritanism, which sought to reform the English church according to God’s Word, especially its worship. When that became impossible due to Laud’s authoritative opposition, the Puritans separated (or were removed) from the English church. Within the Independent wing of Puritan separation, some of them saw a need to apply the regulative principle of worship to infant baptism as well, considering this to be the consistent outworking of the common Puritan mindset. The earliest Baptists believed that the elements of public worship are limited to what Scripture commands. John 4:23 says, “True worshippers will worship the Father in spirit and truth” (see also Matt 15:9). The revealed “truth” of Scripture limits the worship of God to what is prescribed in Scripture. The Second London Baptist Confession 22.1 says:

The acceptable way of worshipping the true God, is instituted by himself, and so limited by his own revealed will, that he may not be worshipped according to the imagination and devices of men, nor the suggestions of Satan, under any visible representations, or any other way not prescribed in the Holy Scriptures.

Because the Bible does not command infant baptism, early Baptists believed that infant baptism is forbidden in public worship, and the baptism of believers alone is to be practiced in worship. This regulative principle of worship limits the elements of public worship to the Word preached and read, the ordinances of baptism and the Lord’s Supper, prayer, the singing of Psalms, hymns, and spiritual songs, and whatever else the Scripture commands.

Many Baptists today have completely abandoned the regulative principle of worship in favor of entertainment-oriented worship, consumerism, individual preferences, emotionalism, and pragmatism. Such Baptists have abandoned the very principle that led to their initial emergence from paedobaptism. One wonders whether a church can depart from a doctrine necessary to the emergence of Baptists in their English context and still rightly identify as a “Baptist” church.

How strange to link the emergence of the PB’s with the Regulative Principle of worship. Hicks believes the PB’s came out from the Church of England. Even if this were true of one or two churches, they certainly do not represent or speak for all PB’s. Their pastors and members came from a wide range of backgrounds.

The Reformed Baptists are not the only group to boast of the Regulative Principle. There are many who claim to worship the Lord according to the commands of Scripture, including those who baptize or sprinkle infants. However, does any one person or group consistently follow this principle? Take, for instance, the ownership of property. Where in scripture is it prescribed that a church should be the owner of land, buildings and other possessions? Where did the churches of the New Testament meet? They gathered almost invariably in houses. Nowhere is it recorded that a church should or did own property. As the Lord’s people are identified as strangers and pilgrims, so their corporate gatherings reflected this, as they remained transient and unanchored to the things of this world. How then can these groups boast about following the Regulative Principle, when they are blatantly violating a clear pattern set out in the New Testament scriptures?

This terminology (regulative principle) and discussion seems to be a matter of concern among the Presbyterians, which is therefore not surprising that the Reformed Baptists have made it one of their distinguishing marks.

2. Covenant Theology. While Reformed paedobaptist churches sometimes insist that they alone are the heirs of true covenant theology, historic Reformed Baptists claimed to abandon the practice of infant baptism precisely because of the Bible’s covenant theology.

First, Reformed Baptists always insist that they alone are the heirs of true PB covenant theology. They do not realize that they embrace a view, set forth in the 1689 Baptist Confession, which was abandoned by the PB’s of the eighteenth century.

Second, ‘historic Reformed Baptists’ have only been in existence since the late 1950’s. They have revived a seventeenth century covenant theology which is not reflective of the mainstream PB’s of succeeding centuries. I find it curious the Reformed Baptists focus all their attention on the years 1633-1689 (56 years) and 1957-2024 (66 years), believing themselves to be the heirs of the seventeenth century PB’s. Do they not know the PB’s introduced several vital reforms between the years 1690-1840 (150 years) and that there remains today a group of churches whose history and teachings are traced back to those years? They call themselves ‘reformed’, yet they are ignorant and/or ignore the reformed teachings of the eighteenth century onwards. A Reformed Baptist is an unreformed PB.

Reformed Baptists agree with Reformed paedobaptists that God made a covenant of works with Adam, which he broke and so brought condemnation on the whole human race (Rom 5:18).

Yes, the PB’s also agree there is a covenant of works.

They also say that God mercifully made a covenant of grace with His elect people in Christ (Rom 5:18), which is progressively revealed in the Old Testament and formally established in the new covenant at the death of Christ (Heb 9:15-16). The only way anyone was saved under the old covenant was by virtue of this covenant of grace in Christ, such that there is only one gospel, or one saving promise, running through the Scriptures.

No, the eighteenth century PB’s did not believe God made a covenant of grace with His elect people in Christ. They believe the covenant of grace is one and the same with the covenant of redemption, and therefore the parties of that covenant are the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit. The conditions of that covenant are the electing love of the Father, the redeeming grace of the Son and the sanctifying power of the Holy Spirit. This covenant is brought to pass throughout the course of history with the Son redeeming and the Spirit sanctifying the elect. One of the reasons the eighteenth century PB’s rejected a covenant of grace God makes with the elect is because it opens the door to the pernicious doctrine of duty-faith, as set forth by men such as Richard Baxter.

Baptist covenant theologians, however, believe they are more consistent than their paedobaptist brothers with respect to covenant theology’s own hermeneutic of New Testament priority. According to the New Testament, the Old Testament promise to “you and your seed” was ultimately made to Christ, the true seed (Gal 3:16). Abraham’s physical children were a type of Christ, but Christ Himself is the reality. The physical descendants were included in the old covenant, not because they are all children of the promise, but because God was preserving the line of promise, until Christ, the true seed, came. Now that Christ has come, there is no longer any reason to preserve a physical line. Rather, only those who believe in Jesus are sons of Abraham, true Israelites, members of the new covenant, and the church of the Lord Jesus (Gal 3:7). In both the Old and New Testaments, the “new covenant” is revealed to be a covenant of believers only, who are forgiven of their sins, and have God’s law written on their hearts (Heb 8:10-12).

The new covenant is an explanation to the Jewish people as a nation of the covenant of redemption (grace). In essence, the nation of Israel was informed that there would be a day coming that the Mosaic Covenant would come to an end and they as a nation would cease to exist. However, they need not fear that God would cast them away, for there is a greater covenant—the covenant of redemption (or from the Jews’ perspective, a new covenant)—which includes the Jews and Gentiles. However, this greater covenant (covenant of redemption) was fully operational since the regeneration of Adam and Eve in the garden of Eden. The blessings of this covenant were extended to elect Gentiles for the first 2,000 years of history, for there were no Jews at that time; it was then extended to the elect Jews and Gentiles for the next 2,000 years, till Christ was born; it continues to be extended to the elect Jews and Gentiles to this day. Far from the teachings of Hicks (and the Reformed Baptists), the new covenant is not a covenant of grace God makes with sinners in time.

Baptists today who adhere to dispensationalism believe that the physical offspring of Abraham are the rightful recipients of the promises of God to Abraham’s seed. But they have departed from their historic Baptist roots and from the hermeneutical vision of the organic unity of the Bible cast by their forefathers. Baptist theologian James Leo Garrett correctly notes that dispensationalism is an “incursion” into Baptist theology, which only emerged in the last one hundred fifty years or so. See James Leo Garrett, Baptist Theology: A Four-Century Study (Macon, GA: Mercer, 2009), 560-570.

And so may it be said of the Reformed Baptists, who have revived the dead orthodoxy of Moderate-Calvinism. Moderate-Calvinism was rejected by the PB’s of the eighteenth century, and eventually failed during the late nineteenth century. Charles Spurgeon experienced this failure with the Downgrade Controversy.

3. Calvinism. Because Reformed Baptists held to the covenant theology (federalism) of the 17th century, they were all Calvinists. The theological covenants of the old federal theology undergirded the early Baptist expressions of their Calvinistic soteriology. When Adam broke the covenant of works, God cursed all human beings with totally depraved natures (Isa 24:5-6), making them unable and unwilling to come to Christ for salvation.

There is a seventeenth century Hyper-Calvinism, expressed in the major confessions of faith (1646 Westminster and 1689 Baptist), which went beyond the teachings of Calvin in a number of doctrinal positions. There is also an eighteenth century Hyper-Calvinism, expressed in the teachings of men such as John Gill, William Huntington and William Gadsby. This too went beyond the teachings of Calvin. However, to distinguish between these hyper views, seventeenth century Hyper-Calvinism became known as Moderate-Calvinism, whereas eighteenth century Hyper-Calvinism retained the name. Moderate-Calvinism subscribes to three permanent and perpetual covenants (redemption, works and grace), whereas Hyper-Calvinism subscribes to two permanent and perpetual covenants (redemption/grace and works).

But God didn’t leave the human race to die in sin; rather, in eternity past, God unconditionally chose a definite number of people for salvation and formed a covenant of redemption with Christ about their salvation (Isa 53; 54:10; Lk 22:29). At the appointed time, Christ came into the world and obeyed the covenant of redemption, fulfilling the terms of the covenant of works that Adam broke. In the covenant of redemption, Jesus kept God’s law perfectly, died on the cross, atoned for the sins of His chosen people, and rose from the dead, having effectually secured salvation for them (Heb 9:12).

“Eternity past” is sloppy language when referring to God’s character. Properly speaking, eternity exists outside of time and should therefore never be expressed within its limitations. It is far better to view eternity as a single point above the timeline, with past, present and future running along the timeline. From this perspective, there is no such thing as eternity past.

God the Father made His choice of the elect prior to viewing them in sin. This He must have done, for it is how He elected and reprobated the angels, and it is the only way the Father could redeem a people from their sins (He must have owned them by electing love prior to their sin, in order to redeem them from it).

There are three branches to the covenant of redemption (grace)—the electing love of the Father, the redeeming grace of the Son and the sanctifying power of the Spirit. I do not see where Hicks provides a full explanation for these engagements of the TriUne Jehovah.

God made the covenant of grace with His elect people (Gen 3:15; Heb 9:15-16) in which He applies all the blessings of life merited by Christ in the covenant of redemption. The Holy Spirit mercifully unites God’s chosen people to Christ in the covenant of grace, giving them blessings of life purchased by Christ’s life and death. God irresistibly draws them to Himself in their effectual calling (Jn 6:37), gives them a living heart (Ezek 36:26), a living faith and repentance (Eph 2:8-9; Acts 11:18), a living verdict of justification (Rom 3:28), and a living and abiding holiness (1 Cor 1:30), causing them to persevere to the end (1 Cor 1:8). All of these life-blessings are the merits of Jesus Christ, purchased in the covenant of redemption, applied in the covenant of grace.

This is nonsense! God does not enter into a covenant with sinners. The blessings of life merited by Christ in the covenant of redemption are applied to sinners by the effectual power of the Holy Spirit also according to the covenant of redemption. The procurement and its application are both brought to pass according to the agreement made between the TriUne Jehovah from eternity. To introduce an additional covenant, supposedly made between God and the sinner, pollutes the gospel of a full and free salvation.

The doctrine of the covenants is the theological soil in which Calvinism grew among early Baptists. Calvinistic Baptists today need to recover the rich federal theology of their forefathers so that the doctrines of grace they’ve rediscovered will be preserved for future generations.

John Calvin was not much concerned with covenant theology in his Institutes of the Christian Religion. His emphasis was on the doctrine of predestination. It was left to succeeding theologians to develop covenant theology, insomuch that the covenantalism of the 1646 Westminster Confession and that of the 1689 Baptist Confession present a framework which is far more robust than that presented by Calvin himself. Why then do the Presbyterians and the Reformed Baptists not permit the eighteenth century PB’s, and Congregationalists, and Independents and Anglicans to make further developments in covenant theology? Is it not possible the covenantal framework of the eighteenth century corrects the many contradictions and errors connected with the covenantal framework of the seventeenth century?

4. The Law of God. Reformed Baptists believe the 10 commandments are the summary of God’s moral law (Exod 20; Matt 5; Rom 2:14-22).

Nonsense! The ten commandments are part of the Mosaic Law. The Mosaic Law was given to and designed for the Jewish people as a nation. It was never given to or designed for the Gentiles, how much less is it given to or designed for believers in Christ. It is certainly not a summary of the moral law. First, every law of God is moral. Whether it be the heart-law, ten commandments or law of Christ—all of God’s laws are moral. Second, the ten commandments are a special application of the heart-law to the Jewish people as a nation—the first four commandments based on loving God supremely; the last six commandments based on loving one’s neighbor as himself. In other words, the heart-law is actually the summary of the ten commandments; the ten commandments is an application of the heart-law to the Jewish people as a nation.

They believe that unless we rightly understand the law, we cannot understand the gospel.

The Reformed Baptists are quite confused on this matter. With reference to the law, some believe it is the law inscribed upon Adam’s heart under the covenant of works, whereas others believe it is the law given to Moses in the form of ten commandments. Thus they interchange the heart-law under the covenant of works with the ten commandments under the covenant of Moses. And if this were not enough, they then insert one of these laws into the covenant of grace, asserting it is the rule of conduct for the believer’s life. As for the gospel, they believe it belongs to a covenant of grace God makes with sinners, activated by saving faith.

The PB’s take the view that every covenant is governed by a law. The covenant of works is governed by the heart-law (loving God supremely and one’s neighbor as one’s self); the Mosaic covenant is governed by the Mosaic Law (inclusive of the so-called moral, civil and ceremonial laws); the covenant of redemption/grace is governed by the gospel law (the soul’s union with Christ).

Although the PB’s agree these covenants must be distinguished along with their laws, yet the Reformed Baptist take a very different view on the law and the gospel. It is for this reason they invariably impose upon the unregenerate duties belonging only to the regenerate (the exercise of saving faith, for instance), and demand of the regenerate duties belonging only to the unregenerate (obedience to the heart-law or ten commandments, for instance).

Furthermore, according to the PB’s framework of covenantal theology, unless one understands the gospel (covenant of redemption/grace), he/she cannot understand the law. The law, under the covenant of works, fits within the framework of the gospel, under the covenant of redemption/grace.

The gospel is the good news that Jesus Christ kept the law for our justification by living in perfect obedience to earn the law’s blessing of life and by dying a substitutionary death to pay the law’s penalty.

The redeeming grace of the Son, which Hicks highlights as the definition for the gospel, is only one of three branches of the good news. The first branch of the gospel is the electing love of the Father; the second branch is the redeeming grace of the Son; the third branch is the sanctifying power of the Spirit. The gospel is the covenant of redemption/grace, wherein the TriUne Jehovah agrees to save His people from their sins. Election explains why Christ came into the world to save sinners; redemption explains how the Holy Spirit is able to impart to sinners new life in Christ. To set forth a full and free gospel requires the preacher to announce the Father’s electing love, the Son’s redeeming grace and the Spirit’s regenerating power.

But the gospel isn’t only a promise of justification. It’s also the good news that Christ promises graciously to give the Holy Spirit to His people to kill their lawlessness and to make them more and more lawful. Titus 2:14 says that Christ “gave himself for us to redeem us from all lawlessness and to purify for himself a people for his own possession, who are zealous for good works.”

The gospel does not promise to give the Holy Spirit, it is the power of God unto salvation by which the Holy Spirit regenerates the soul. The Father drew up a twofold plan of salvation for His elect people—(1) justifying them by the redemption that is in Christ Jesus; (2) regenerating them by the power of the Holy Spirit. Both acts of salvation are accomplished by Jehovah—the sinner cannot justify himself/herself by earning righteousness through good works; nor can the sinner regenerate himself/herself by making a decision for Jesus or exercising saving faith.

The Holy Spirit, in His work of sanctification, does not make His people “more and more lawful”. This is descriptive of the fallacious doctrine of progressive sanctification. In regeneration, the soul is united with Christ, by virtue of which the life and virtues of Christ flow into the soul, making the sinner alive unto God and enabled to exercise saving faith in Christ. This spiritual union with Christ is called a new nature, often referred to in scripture as the “spirit”, created in righteousness and true holiness. The new nature cannot be made more righteous or more holy, for “that which is born of the Spirit is spirit”—it cannot be changed. However, there remains in the soul an old nature, often referred to in scripture as the “flesh”, which is corrupt according to the deceitful lusts. The old nature cannot be reformed or improved, for “that which is born of the flesh is flesh”—it cannot be changed. These natures exist together in the soul, resulting in the experience described by the Apostle Paul in Romans 7. Whereas the new nature may grow in grace, expressive of good works, it does not progress in holiness.

The Second London Baptist Confession, 19.5 says:

The moral law does for ever bind all, as well justified persons as others, to the obedience thereof,(10) and that not only in regard of the matter contained in it, but also in respect of the authority of God the Creator, who gave it;(11) neither does Christ in the Gospel any way dissolve, but much strengthen this obligation.(12)

10. Rom 13:8-10; Jas 2:8,10-12 11. Jas 2:10,11 12. Matt 5:17-19; Rom 3:31

So what? The PB’s have never used the 1689 Confession as an authoritative document for faith and practice. Only the Reformed Baptists look to it in that way. But to the point of the nineteenth article, the scriptures never identify the heart-law under the covenant of works as the “moral law”. Nor do the scriptures identify the ten commandments under the mosaic covenant as the “moral law”. Nor do the scriptures separate the ten commandments from the other commandments given to Moses under that covenant. Men have made these innovative distinctions based on a flawed understanding of the law and the gospel. The fact is, every covenant is governed by its own law. Every law God puts within a covenant is “moral”. The heart-law under the covenant of works is “moral”; all of the laws given to Moses under that covenant are “moral”; the gospel law under the covenant of redemption/grace is “moral”. That law and covenant which is binding upon the unregenerate is the heart-law and the covenant of works God made with Adam. That law and covenant which is binding upon the regenerate is the gospel law and the covenant of redemption/grace. That law and covenant which was binding upon the Jewish people as a nation is the ‘moral’/civil/ceremonial law and the mosaic covenant. However, the 1689 Confession sets forth an additional covenant (of grace) God makes with sinners, extrapolating from the mosaic covenant the ten commandments and making it that law which governs this so-called covenant of grace. Consequently, the two permanent and perpetual covenants (that of works and redemption/grace) are mixed together with the earthly and temporary covenant God made with Moses, resulting in a convoluted mess which resembles neither the heart-law under the covenant of works nor the gospel law under the covenant of redemption/grace. Whereas the PB’s of succeeding centuries buried the covenantal framework of the 1689 Confession, the Reformed Baptists have resurrected it.

Therefore, while justified believers are free from the law as a covenant of works to earn justification and eternal life (Rom 7:1-6), God gives them His law as a standard of conduct or rule of life in their sanctification (Rom 8:4, 7).

This is legal sanctification. Hicks (and the Reformed Baptists) believes that while the regenerate sinner is free from the law as a covenant of works to earn justification and eternal life, yet he/she is bound to the law as a covenant of grace to become more holy and live a fuller spiritual life. The PB’s believe that the righteousness of Christ is judicially imputed to the elect from eternity, and experientially imparted to the elect at the appointed time in history by the regenerating power of the Holy Spirit. Regeneration is the soul’s union with Christ, whereby He is made unto the regenerate sinner wisdom, and righteousness, and sanctification, and redemption. The soul’s union with Christ is the gospel law—a living and vital law, with the life of Christ flowing into the soul, making the sinner alive unto God; as well as the virtues of Christ flowing into the soul, which are fruits of that union (among which is saving faith). The rule of conduct for the believer’s life, therefore, is not the heart-law under the covenant of works, or the ten commandments under the mosaic covenant, but the gospel law under the covenant of redemption/grace.

God’s moral law, summarized in the 10 commandments (Rom 2:14-24; 13:8-10; Jas 2:8-11), including the Sabbath commandment (Mk 2:27; Heb 4:9-10), is an instrument of sanctification in the life of the believer.

Once more, every covenant is governed by its own law, and if it is a covenant established by God, then its law is always moral. Henceforth, the heart-law, ten commandments and gospel law are all moral laws. Hicks (and the Reformed Baptists) want to replace the gospel law of the covenant of redemption/grace, with the ten commandments belonging to another covenant. The issue, therefore, is not whether the believer is under a ‘moral’ law, but rather, which ‘moral’ law is the believer under?

Believers rest in Christ for their total salvation.

Hicks (and the Reformed Baptists) certainly do not believe regenerate sinners rest in Christ for their total salvation. They believe they rest in Christ for their justification and eternal life, but rest in their obedience to the ten commandments for their sanctification and spiritual walk.

Christ takes their burdens of guilt and shame, and His people take upon themselves the yoke of His law, and they learn obedience from a humble and gentle Teacher.

The yoke of Christ is not the heart-law or the ten commandments. The yoke of Christ is the regenerate sinner’s spiritual union with Him—that living law (the law of Christ) whereby the life and virtues of Christ flow into the soul. Hicks (and the Reformed Baptists) would have us believe the law of Christ is the ten commandments. How bizarre!

1 John 5:3 says, “For this is the love of God, that we keep His commandments. And His commandments are not burdensome.”

Yes, by virtue of the regenerate sinner’s spiritual union with Christ (which is the gospel law, or the law of Christ), the fruits of that union grow and blossom, finding expression in good words and works. Every good word and work of a believer is the result of the fruits of his/her new nature in Christ (love, joy, peace, gentleness, faith, etc). It is for this reason the commandments of God are not burdensome. While the scriptures are full of godly precepts (commandments) set upon believers to follow, it is the Spirit of God who works in the believer the virtues of Christ, both to will and to do of His good pleasure, enabling the believer to work out his/her own salvation with fear and trembling.

Baptists who hold to new covenant theology, or progressive covenantalism, do not have the same view of the law as the dominant stream of their Baptist forebears.

Hicks (and the Reformed Baptists) believe their views on progressive sanctification represent the mainstream view of the PB’s throughout the centuries. He (and they) are wrong!

5. Confessional. Most of the early Baptists, both in England and in America, held to the Second London Baptist Confession of 1677/1689. While certainly not all Calvinistic Baptists subscribed to this confession, it was the main influence among Baptists in England and America after its publication.

Where is the evidence? Show us the PB churches who subscribed to the 1689 Confession between the eighteenth to the twenty-first centuries. Show us the PB preachers who expounded the 1689 Confession, or referenced it in their sermons and writings, or used it as an authoritative document in their disputations and discussions. By the mid-eighteenth century, the 1689 Confession became obsolete, with the majority of PB’s abandoning its covenantal framework and convoluted teachings. Not only did each congregation draw up its own statement of faith, the articles reflected the High (Hyper) Calvinism of John Gill’s covenantal framework. Hicks (and the Reformed Baptists) assume the 1689 Confession must have been a dominate influence among the PB’s throughout the centuries, because it is a dominate influence among the Reformed Baptists of the last sixty years. They are mistaken.

This confession, based on the Westminster Confession (Presbyterian) and the Savoy Declaration (Independent), was originally edited and published in 1677, but formally adopted by Baptist churches in 1689 after English persecution lifted.

The 1689 Confession was never designed to be used as a standard of orthodoxy unifying the PB denomination. It was drawn up and adopted by churches for the sole purpose of earning the respect of other reformed groups and evading persecution from a tyrannical government. Benjamin Keach, for instance, one of the poster children for the Reformed Baptists, refused to recommend the 1689 confession to his church, choosing instead to draw up his own statement of faith for the church eight years later. The reason the 1689 Confession now has such prominence, is because the Reformed Baptists, aspiring to live up to the standards of their Presbyterian big brothers, have felt the need to be ‘confessional’. The only PB’s I know who have felt that same need are the Gospel Standard, but they subscribe to their own articles of faith reflective of the eighteenth century PB teachings.

Historic Reformed Baptists were thoroughgoing confessionalists.

Yes, historic Reformed Baptists are thoroughgoing confessionalists. Their movement began in 1957, giving to them a history just short of seventy years. Their movement has now existed longer than the seventeenth century PB’s (1633-1689). Of course, to give substance and historic authority to their movement, they lay claim to the seventeenth century PB’s, but as I have been pointing out, they are two separate groups. Just because the Reformed Baptists have adopted the 1689 Confession and revived its covenantal framework, does not give them the right to claim the history and heritage of the PB’s. The fact is, the Reformed Baptists are thoroughgoing confessionalists, but that has never been true for the PB’s.

They were not bare “biblicists.” Biblicists deny words and doctrines not explicitly stated in Scripture, and they deny that the church’s historic teaching about the Bible has any secondary authority in biblical interpretation.

I am astounded by the remaining statements of Hicks. Since when has it been wrong to be a ‘biblicist’? Does not Hicks believe in scripture alone? Ah, he addresses that point below, so I will come back to it then. Hicks does, however, define a biblicist as one who denies words and doctrines not explicitly stated in scripture. Well, this may be one way some people identify as a biblicist. But another way of defining it is one who conforms his/her views to the teachings of scripture—not to the teachings of a confession, but to the teachings of scripture. In this sense all Baptists are bare “biblicists”. When Hicks speaks about “the church’s historic teachings about the Bible”, to which church is he referring? Is this a universal church inclusive of all Christians and their denominations? Or is this a universal church exclusive of Christians belonging to the Baptist denomination? Or is this a universal church represented by high ranking pastors and theologians? It sounds a lot like a Roman Catholic Church and its high ranking clergy. Is Hicks suggesting there is some kind of universal church and its clergy which has been set up by God to lord over His heritage?

The early Baptists, however, did not believe that individual church members or individual pastors should interpret the Bible divorced from the historic teaching of the church (Heb 13:7).

Wow! Really!? God forbid that a Christian should study the scriptures without the dictation of a universal church and her authorized teachers. Nonsense!

They believed that the Bible alone is sufficient for doctrine and practice, but they also believed the Bible must be explained and read in light of the church’s interpretive tradition (1 Tim 3:15), which uses words other than the Bible (Acts 2:31 is one refutation of biblicism, since it explains Psalm 16 in words not used in that Psalm).

Is this not the position of the Roman Catholic Church? They believe the Bible is sufficient for doctrine and practice, but they also believe the Bible must be explained and read in light of the ‘church’s’ interpretive tradition. This is shocking language coming from one who claims to be a Baptist.

Reformed Baptists believed that their theology was anchored in the church’s rich theological heritage and that it was a natural development of the doctrine of the church in light of the central insights of the Reformation (sola Scriptura: no baptizing infants; sola fide: only converts are God’s people).

Once more, to which church is Hicks referring? Is this all of the seventeenth century PB churches? Do the eighteenth and nineteenth century PB churches count? If so, then which of these churches are given divine authority to speak for the rest, for none of them agreed on every point of doctrine? Or, is Hicks referring to the Church of England, as it is out from Anglicanism he believes the PB’s emerged. If it is the Church of England’s rich theological heritage the Reformed Baptists believe their theology is anchored, then why have they departed from that faith?

Under the guise of upholding Sola Scriptura, many Christians today seek to read the Bible independently and come to their own private conclusions about what it means without consulting the church’s authorized teachers or the orthodox confessions of faith.

I have often pointed out the contradictions of the Reformed Baptists’ confessionalism, where they boast of sola scriptura, but interpret it by the authoritative statements of the 1689 Confession. What makes one’s private interpretation of scripture any less dangerous than one’s confessional interpretation? If the confessional statement is wrong, and it is used as the infallible rule by which to interpret scripture, how is this better than one coming to the scriptures without the restraints of an erroneous document? Plus, Hicks speaks about the need to consult the church’s authorized teachers. Once again, what exactly is this church, and who are the authorized teachers? Who authorized them? Is he speaking about the prophets and the apostles? If so, then may we not read what they say—the scripture itself—and interpret their writings? Or, is he speaking about the sixteenth and seventeenth century pastors and theologians? If so, when did God make these men the authorized teachers of His book?

But that’s not what Sola Scriptura historically meant. Scripture teaches that the church is the “pillar and support of the truth” (1 Tim 3:15).

Which church? A universal church of all believers? Or the local church of baptized believers who have covenanted to follow the commands of Christ? Is it not the local church that Christ has designed to serve as the pillar and ground of the truth? If so, then it is the Lord’s regenerate people who gather together for worship and scripture study, whose responsibility it is to hold fast that form of doctrine and proclaim it to their community. May the church members consult other teachers and writings? Yes, but they are not bound by any creed or confession or teacher. Nothing and no one is to lord over them. Christ is their Head, the Spirit of God is their Teacher and together they grow in grace and in the knowledge of the Lord Jesus Christ.

The church as a whole is charged with interpreting the Bible, and God has authorized teachers in the church throughout history.

“The church as a whole”. Which church? I keep pressing this point, because Hicks nurtures an anti-Baptist view on the church and scripture authority. Which teachers has God authorized in the church throughout history? Is not every God called evangelist and pastor an authorized teacher in the churches throughout history? If so, then should not each church, with her own pastor, study the scriptures together and follow the Lord in the light He gives to them? Why is Hicks insisting on churches yielding themselves to an elite group of teachers only he recognizes to be authorized by God to interpret the scriptures?

Therefore, while every individual Christian is responsible to understand Scripture for himself, no Christian should study the Bible without any consideration of what the great teachers of the past have taught about the Bible.

What about the great teachers of the present? Hicks (and the Reformed Baptists) elevate the writings of the past to a position of authority not sanctioned by God. They do not believe every Christian is responsibility to understand the scripture for himself/herself. They believe every Christian is responsible to follow the teachings of the 1689 Confession, and if anyone departs from its articles, he/she is counted a heretic. Rather than interpreting the 1689 Confession in light of the scriptures, bringing its teachings under the scrutiny of God’s Word, they interpret the Bible in light of the 1689 Confession, conforming God’s Word to the teachings of the seventeenth century “authorized teachers”. I see no difference between the dictates of Rome over its people, and that of the Reformed Baptists over its people.

The majority of historic Reformed Baptists held to the Second London Baptist Confession of 1689 because they believed it is a compendium of theology that best summarizes the teaching of Scripture in small compass.

All historic Reformed Baptists (1957-2024) hold to the 1689 Confession, not because it best summarizes the teaching of scripture in small compass, but because they have made it the infallible rule by which to interpret the Bible. Just listen to their sermons and podcasts—they support their teachings and explain the scriptures in light of the 1689 Confession. It is difficult for those who live in the Reformed Baptist bubble to see these things objectively. But for those who are not under the lordship of their rule, their undying devotion to the creeds and confessions of men is quite alarming.

“And that because of false brethren unawares brought in, who came in privily to spy out our liberty which we have in Christ Jesus, that they might bring us into bondage: to whom we gave place by subjection, no, not for an hour; that the truth of the gospel might continue with you.”—Galatians 2:4,5

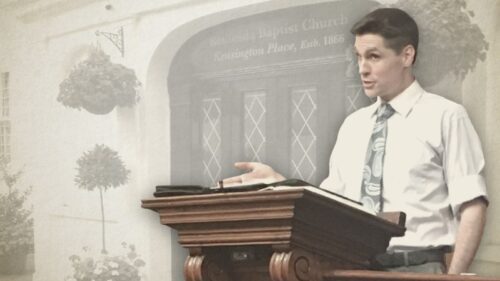

Jared Smith served twenty years as pastor of a Strict and Particular Baptist church in Kensington (London, England). He now serves as an Evangelist in the Philippines, preaching the gospel, organizing churches and training gospel preachers.

Jared Smith on Eldership

Jared Smith on the Biblical Covenants

Jared Smith on the Gospel Law

Jared Smith on the Gospel Message

Jared Smith on Various Issues

Jared Smith, Covenant Baptist Church, Philippines

Jared Smith on Bible Doctrine

Jared Smith on Bible Reading

Jared Smith's Studies in Romans

Jared Smith's Hymn Studies

Jared Smith's Maternal Ancestry (Complete)

Jared Smith's Sermons