3 18th Century Covenant Theology Versus The Presbyterians

I’d like to welcome you back to another study in the Word of God. In our previous studies, I presented to you the Scripture structure for 2 Thessalonians 2:13-17. There is a twofold statement on the privilege of brotherhood—In verse 13 Paul thanks God for their salvation—“But we are bound to give thanks alway to God for you, brethren beloved of the Lord,”; but in verse 15 he is exhorting them to stand fast in their salvtion—“Therefore, brethren, stand fast, and hold the traditions which ye have been taught, whether by word, or our epistle.” The privilege of brotherhood, my dear friends, is to experience the new birth of which Paul makes reference when thanking God for the salvation of those living in Thessalonica, and then to stand fast in the faith according to the gospel that saved them. We then have a twofold statement on the gospel of our salvation—In verses 13 and 14, the three branches of the gracious covenant are highlighted—“because God hath from the beginning chosen you to salvation through sanctification of the Spirit and belief of the truth: whereunto he called you by our gospel, to the obtaining of the glory of our Lord Jesus Christ.” And then in verses 16 and 17, there are four blessings of the gracious covenant imparted to regenerate sinners—“Now our Lord Jesus Christ himself, and God, even our Father, which hath loved us, and hath given us everlasting consolation and good hope through grace, comfort your hearts, and stablish you in every good word and work.”

But then, taking a closer look at verses 13 and 14, where we are given the three branches of the gracious covenant, we discovered there are four parts to this text. There’s a twofold statement on the first branch of the gracious covenant—the role assumed by God the Father. First, He has chosen you to salvation from eternity, a reference to His electing love—“because God hath from the beginning chosen you to salvation.” Second, He calls you by our gospel, at the appointed time in history, which is a reference to His experiential love, for what He chooses from eternity is experienced by us, His people, in time—“whereunto he called you by our gospel.” We then have a twofold statement on the second and third branches of the gracious covenant: First, the role assumed by God the Spirit, sanctification which leads to belief of the truth—“through sanctification of the Spirit and belief of the truth.” This, of course, is a reference to regeneration by the effectual power of the Holy Spirit. Second, the role assumed by God the Son—“To the obtaining of the glory of our Lord Jesus Christ.” This is a reference to the sinner being freely justified by the redemption that is in the Lord Jesus Christ..

I say, therefore, we have here the three branches of the gracious covenant, or the Covenant of Grace. To be sure you understand what I mean when I use this expression, allow me to mark it out for you in a diagram. The Covenant of Grace is drawn up from eternity between the three Persons of the Godhead on behalf of Their elect people. The Father sets this people part by electing love; the Son sets them apart by redeeming grace; and the Spirit sets them apart by sanctifying power. This is an absolute covenant between the Persons of the Godhead, brought to pass in time, with the Spirit of God regenerating and sanctifying all those given to Him by the Father and the Son; and the Son, when the fulness of time came, redeeming all those given to Him by the Father. In no sense is this covenant made with sinners in time, or even with the elect from eternity, and therefore it precludes the doctrines of duty faith, the free offer and legal sanctification.

Now, what I’ve presented to you from this text and in this diagram is what 18th century preachers and theologians, such as Benjamin Keach and John Gill, call the Covenant of Grace. And it is this understanding of the Covenant of Grace which forms the basis for 18th century Hyper-Calvinism. I say 18th century Hyper-Calvinism, because nowadays, the covenantal framework embraced by mainstream Reformed churches is that of 17th century Hyper-Calvinism, which is a very different covenant theology than that presented to you in this diagram and from our text.

For instance, if you are at all familiar with the teachings of the Presbyterians and the Reformed Baptists, you will know they think of the Covenant of Grace in a very different way, because their views are based on the confessional statements of the 17th century. When they speak about the Covenant of Grace, they believe it is based upon a Covenant of Redemption, but made between God and the sinner, wherein life and salvation is offered to sinners, on condition of saving faith, with the moral law serving as a rule of conduct for the believer’s life. You see, they believe the Covenant of Grace is made between God and sinners in time, wherein the preacher freely offers life and salvation to them, with saving faith the condition of their salvation, and the moral law the rule to guide them in their walk with God. This, my dear friends, is a very different covenant from that which I’ve presented to you in this diagram, and again, quite different from that which is set forth in our text.

For the next four studies, I would like to examine these different views on the Covenant of Grace.

For this study, I will give a brief overview on the historic development of covenant theology during the 16th and 17th centuries, and then I will hone in on the teachings of Presbyterianism, represented by the 1646 Westminster Confession of Faith.

For our next study, I will examine the teachings of the Reformed Baptists, represented by the 1689 Baptist Confession of Faith, followed by a number of reforms to covenant theology which began to appear during the first half of the 18th century. In particular, we will consider the covenant theology of an 18th century Presbyterian named Thomas Boston, whose reforms are often mistaken to be the same as those introduced by Benjamin Keach and John Gill.

For our third study, I will examine the reforms to covenant theology introduced by Benjamin Keach in 1692 and developed by John Gill throughout the course of his gospel ministry during the greater part of the 18th century.

For our fourth study, I will demonstrate how Gill’s reforms to covenant theology were not only embraced by a large section of the Particular Baptist churches, but also many belonging to the Independent and Anglican denominations.

Let’s begin this study with a brief overview on the historic development of covenant theology during the 16th and 17th centuries, with a particular look at Presbyterianism represented by the 1646 Westminster Confession of Faith.

The Presbyterians emerged during the 1560s under the teachings of John Knox, at which time the Church of Scotland was organized; another group was also formed during the 1640s, around the time the English Parliament organized the Westminster Assembly for the purpose of drawing up a statement of faith which best reflected the doctrinal position of the Anglian Church. The result was the Westminster Confession of Faith completed in 1646, published in 1647. However, rather than this statement serving as a doctrinal expression for the Anglican Church, it became the standard for the Presbyterians. From that time till now, the Presbyterians have always identified as a confessional church, leaning upon this 17th century statement of faith.

Now, one of the unique features about this confessional statement, compared to others which came before it, was its teaching on the covenants. The Westminster Assembly constructed a covenantal framework around which to organize the various branches of theology. It may surprise you to learn, covenant theology, as we think of it today, is a relatively new framework for systematic theology. However, that isn’t to say Christians before that time didn’t believe in or teach the Bible covenants—they did. The Bible speaks about covenants, in both the Old and New Testament Scriptures, so both Old and New Testament saints were familiar with the term and its connotations and teachings—to be sure, Abraham, Moses, David, Isaiah, Jeremiah, Paul and Peter were familiar with its teaching—they taught about it. We also find references to Bible covenants in the writings of the church fathers during the second to sixth centuries. And we find references to Bible covenants in the writings of the great Reformers during the Protestant Reformation. However, throughout these centuries, there was not yet a robust framework of covenant theology that had been developed. People’s view and understanding of the covenants, outside of the biblical narrative, was loose and uninformed. But this began to change with the writings of men such as John Calvin, who between 1536-1559 published his “Institutes of the Christian Religion”. Throughout this work, Calvin referred to a Covenant of Grace, but only by that name a few times. He spoke of this covenant as a free covenant, a gospel covenant, an everlasting covenant, a covenant of peace and most often simply as the covenant. He understood this to be a covenant between God and the sinner, wherein the blessings of Christ’s redeeming grace are applied to the elect. There were other Reformers at this time, such as Henry Bullinger, who also spoke of a Covenant of Grace, so this was not something unique to Calvin’s theology. With reference to Calvin, he did not speak directly about a covenant made between God and Adam before the Fall (what we know to be the Covenant of Works), nor did he speak directly about a covenant made between the Father and the Son from eternity (what we know to be a Covenant of Redemption). That isn’t to say he rejected these covenants—there are indirect references to something like them in his writings—but Calvin himself never developed a covenant theology which brought these things together.

It wasn’t until 1595 that a Presbyterian preacher named Robert Rollock referred to the Covenant of Works by name, in his book on Questions and Answers. Thereafter, we begin to find references among the Reformers and Puritans to a Covenant of Works God made with Adam, requiring of him perfect obedience to the law, and a Covenant of Grace God makes with sinners, requiring of them faith in Christ. The Bible teachings on the law was then placed under the Covenant of Works and its teachings on the gospel was placed under the Covenant of Grace. This was the first established framework of covenant theology—developed at the turn of the 17th century.

Forty-five years later, in 1645, another Presbyterian preacher named David Dickson, delivered a lecture to the General Assembly of the Scottish Church, wherein he made reference to a Covenant of Redemption. This is the first time the expression occurs in the writings of the 17th century. According to this covenant, Dickson taught there is an agreement between the Father and the Son from eternity concerning the redemption that Christ would accomplish in time. There is no record of the delegates at the Assembly raising questions or disagreeing with this teaching, which suggests it was not something strange or new to these Presbyterian ministers.

By 1645, we therefore have three major covenants which form the basic framework of covenant theology:

A Covenant of Works, between God and Adam before the Fall, requiring of him perfect obedience to the law.

A Covenant of Grace, between God and the sinner, requiring of him saving faith in Christ.

A Covenant of Redemption, between the Father and the Son from eternity, concerning the redemption of the elect.

However, the primary covenants were those of Works and Grace, whereby a clear distinction was made between the gospel, under this conditional Covenant of Grace between God and sinners, requiring of them saving faith in Christ, and the law, under this conditional Covenant of Works between God and Adam before the Fall, requiring of him perfect obedience to the law. The idea of a Covenant of Redemption was secondary to, or a backdrop for, these other two, central and primary covenants.

Now, it was less than two years after David Dickson coined the label, the Covenant of Redemption, the 1646 Westminster Confession of Faith was put to press.

I will now read for you Article 7 of this confession where reference is made to covenant theology:

“The first covenant made with man was a covenant of works,”

This is that Covenant of Works introduced by Robert Rollock and developed by the Reformers and Puritans.

“wherein life was promised to Adam; and in him to his posterity, upon condition of perfect and personal obedience.”

This covenant was made between God and Adam before the Fall, on behalf of the human race, requiring perfect obedience to the law inscribed upon the heart.

“Man, by his fall, having made himself incapable of life by that covenant, the Lord was pleased to make a second, commonly called the covenant of grace;”

This is that Covenant of Grace mentioned by men such as John Calvin and Henry Bullinger, and developed by the Reformers and Puritans.

“wherein He freely offers unto sinners life and salvation by Jesus Christ; requiring of them faith in Him, that they may be saved,”

This covenant is made between God and Adam after the Fall, requiring of sinners saving faith in Christ, having life and salvation freely offered to them in the gospel.

“and promising to give unto all those that are ordained unto eternal life His Holy Spirit, to make them willing, and able to believe.”

Please note, and note it well, the Holy Spirit Himself, as a Person, is not a Party in this covenant. The Godhead in three Persons is the party with sinners, but the Holy Spirit as a distinct Person is not Himself a party in this covenant. He is only a promised helper to sinners, to make them willing and able to believe.

Henceforth, we have in the 1646 Westminster Confession of Faith reference to a Covenant of Works made with Adam before the Fall, requiring of him perfect obedience to the law; and a Covenant of Grace made with sinners, wherein life and salvation is freely offered to them on condition of their faith in Christ. However, as you have seen, there is not a reference to the Covenant of Redemption. In fact, this label doesn’t appear in the Westminster Confession. Having said that, we do find a reference to it in the eighth article, where it reads:

“It pleased God, in His eternal purpose, to choose and ordain the Lord Jesus, His only begotten Son, to be the Mediator between God and man…”

Now, this is certainly a reference to the Covenant of Redemption—that agreement between the Father and the Son from eternity about the redemption of the elect.

This, then, is the basic covenantal framework of the 1646 Westminster Confession of Faith, maintained by the Presbyterians. There are three main covenants—that of Grace, Works and Redemption. However, the most significant of these covenants is that of Grace and Works, with the Gospel placed under the jurisdiction of the one, and the Law placed under the jurisdiction of the other. Furthermore, there is a free offer of the gospel, supported by the doctrine of duty faith, which belongs to the nature and conditions of the Covenant of Grace.

Now, that is the backdrop on how these three covenants emerged and developed into a system of teaching, with the 1646 Westminster Confession serving as one of the first formal statements on the subject.

We may therefore ask, given our modern context of Reformed teachings, “How do Presbyterians today interpret the covenant theology of the 1646 Westminster Confession?” Well, I suggest you need to let each person answer that question himself, because I have found such a variety of views, it is not easy nailing down exactly how modern day Presbyterians understand their covenant theology. As the old saying goes, Ask one hundred people a question, and you get a hundred different answers. Nevertheless, for the purpose of this study, I have selected a well known and highly respected Presbyterian preacher and theologian—the late R. C. Sproul—to tell us how he understood the covenant theology of Presbyterianism. Now, of course, R. C. Sproul was the Founder of Linonier Ministries—its headquarters is in Orlando, Florida. In his book, “What Is The Reformed Faith”, he presents the following chart highlighting the basic details on these three major covenants:

For the Covenant of Redemption, he has listed for the parties the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit. The Father is the initiator and the agreement was drawn up from eternity past (his language, not mine). There are no conditions, rewards or penalties for this covenant.

For the Covenant of Works, the parties are God and human beings. God is the initiator and the agreement was made at creation before the Fall. The condition is perfect obedience to the law inscribed upon the heart, life is the reward for obedience and physical and spiritual death is the penalty for disobedience.

For the Covenant of Grace, the parties are God and sinful human beings. God is the initiator and the agreement was made after the Fall. The condition is faith in Christ, spiritual life is the reward and spiritual death is the penalty for unbelief.

We therefore note—what Sproul means by a Covenant of Grace is an agreement between God and sinners; it is a conditional covenant requiring the unregenerate sinner to exercise saving faith; if the unregenerate sinner exercises saving faith, God will reward him/her with eternal life; but if the unregenerate sinner doesn’t savingly believe on Christ, God will punish him/her with spiritual death.

As for the Covenant of Redemption, Sproul views it as God’s decree or purpose in salvation, wherein He sets out the plan of salvation that will be brought to pass in time under the Covenant of Grace. This he makes perfectly clear in his explanation of this chart:

“This covenant defines the roles of the persons of the Trinity in redemption. The Father sends the Son and the Holy Spirit. The Son voluntarily enters the arena of this world by incarnation. He is no reluctant Redeemer. The Holy Spirit applies the work of Christ to us for our salvation. The Spirit does not chafe at doing the Father’s bidding. The Father is pleased to send the Son and the Spirit into the world, and they are pleased to carry out their respective missions.”

Henceforth, Sproul views the Covenant of Redemption to include the redeeming grace of God the Son and the sanctifying power of God the Spirit, in the salvation of the elect. However, he does not include the electing love of God the Father as part of this agreement, as he views that as something which was determined as an act of predestination, rather than covenant agreement. So, the doctrine of election, as you can see from the overview of these three covenants, does not actually find a place; it is something that precedes or exists outside of these covenants. And that is an important point to note, for when you compare this covenantal framework with that I presented at the beginning of the study, you see that the electing love of the Father is very much part of the Covenant of Grace, clearly set forth in 2 Thessalonians 2.

Now, you also notice Sproul marks down nothing for the conditions of the Covenant of Redemption. I suppose what he means by that, to be fair to him, is that there are no conditions placed upon sinners under its terms and promises. However, this covenant does have conditions—it was required God the Son assume the role of redeeming grace and God the Spirit assume the role of sanctifying power, and therefore these should have been marked down as the conditions for the Covenant of Redemption. And of course, I would add to the conditions the electing love of God the Father, for without the Father setting apart a people as objects of His special love, there would be no one to redeem or sanctify.

As for the reward, the TriUne Jehovah receives unto Himself those whom He has set His everlasting love upon, those who have been purchased by the precious blood of Christ, those who have been regenerated by the Spirit of God, and of course, He also receives the honor and glory for saving them from their sins.

Now, the important thing to note about this covenantal framework of the 1646 Westminster Confession of Faith and of R. C. Sproul’s explanation of it is this: It distinguishes between a Covenant of Redemption which is viewed as God’s eternal blueprint for salvation, and a Covenant of Grace which is viewed as God bringing to pass His eternal blueprint throughout the course of history. Indeed, this view is shared by many theologians and preachers. Take for instance, Louis Berkhof, a Presbyterian theologian. In his “Systematic Theology”, he also distinguished between the Covenants of Redemption and Grace:

“The counsel of redemption is the eternal prototype of the historical covenant of grace…The former is eternal, that is, from eternity, and the latter, temporal in the sense that it is realized in time. The former is a compact between the Father and the Son as the Surety and Head of the elect, while the latter is a compact between the triune God and the elect sinner in the Surety. The counsel of redemption is the firm and eternal foundation of the covenant of grace. If there had been no eternal counsel of peace between the Father and the Son, there could have been no agreement between the triune God and sinful men. The counsel of redemption makes the covenant of grace possible.”

It is quite clear, therefore, that these men viewed the Covenant of Redemption as the eternal blueprint, or plan, for all that God would do in time, realized in a Covenant of Grace God makes with sinners throughout the course of history. Henceforth, they relegate to the backdrop of history this Covenant of Redemption, bringing to the forefront a Covenant of Works God made with Adam before the Fall and a Covenant of Grace God makes with sinners, holding these two covenants up as the main covenants with which the members of the human race are in relationship to or with God. And you see, they do not view the gospel as belonging to the Covenant of Redemption, but rather, to the Covenant of Grace, which is an important point to recognize, for in this instance their gospel message is based largely on the duties and obligations of sinners, rather than the free grace of God the Father in Christ by His Spirit. Henceforth, what they mean by the gospel is quite a different thing that what Paul refers to in 2 Thessalonians 2.

Alright, well, I must bring this study to a close, and I do so by comparing this covenantal framework of the 1646 Westminster Confession with that I presented at the beginning of this study.

First, I agree that there is a Covenant of Works God made with Adam before the Fall, on behalf of the human race, requiring of him perfect obedience to the law inscribed upon his heart. I believe this covenant is renewed with every person when they come into the world, and, because we all come into the world under the headship of Adam, we are by default conceived in sin, shaped in iniquity and therefore spiritually dead. So on this point—in terms of this covenant—there is agreement with the 1646 Westminster Confession.

Second, I do not believe there is a Covenant of Grace God makes with sinners after the Fall. I therefore do not believe there is a free offer of life and salvation which is intrinsic to that covenant, nor do I believe saving faith is a duty imposed upon the unregenerate which is corollary to that covenant, nor do I believe this covenant reveals the gospel, or the gospel reveals this covenant, nor do I believe a rejection of this covenant aggravates a sinner’s damnation or is the cause of a sinner’s condemnation. All of these things I deny. I do not believe the Scriptures speak of a covenant of this kind nor of these components that have been put within this covenant.

Third, I believe there is a Covenant of Redemption made from eternity between the three Persons of the Godhead. I also believe, as set forth by R. C. Sproul and Louis Berkhof, that this covenant is the blueprint of God’s saving grace on behalf of His elect people. However, in addition to what Sproul and Berkhof have said about this covenant, I would go further and say that this covenant begins with and includes the electing love of God the Father. From eternity, the Father took the lead in this covenant, by setting apart a people unto Himself as objects of His special love. These people the Father gave to His Son, appointing Him to serve as their Redeemer. These people the Father and the Son gave to the Spirit, appointing Him to serve as their Sanctifier. Thus, we have in this covenant a full and complete salvation accomplished by God and on behalf of His elect people. God the Father freely justifies the elect sinner from eternity through the redemption that is in Christ Jesus, and God the Father freely calls the elect sinner in time through the sanctifying power of the Holy Spirit—justification and sanctification flow from the self-same covenant. And you see, all that the TriUne Jehovah agreed to from eternity, is brought to pass throughout the course of history in perfect measure. Each Person of the Godhead assumes a role in the salvation of His people—the Father assumes the role of electing love; the Son assumes the role of redeeming grace; the Spirit assumes the role of sanctifying power. This is the only covenant God has made for the salvation of sinners, and it is this which is revealed in Scripture to be the gospel unto salvation. It is a threefold gospel, beginning with the electing love of the Father, issuing in the redeeming grace of the Son and experienced by the sanctifying power of the Holy Spirit. This is the gospel of your salvation. This is the gospel, the power of God unto salvation. This is the gospel of free and sovereign grace. It is agreed upon from eternity between the three Persons of the Godhead. And all that the TriUne Jehovah has agreed to accomplish under the terms and promises of this covenant from eternity, is brought to pass in time throughout the course of history—the Son assuming a human nature in the Person of the Lord Jesus Christ as well as the Holy Spirit regenerating the elect, from Adam and Eve to the end of the world. This covenant precludes a free will offer of life and salvation to the unregenerate, which not only contradicts the certainty of justification, but undermines a full and final redemption. It also precludes the pernicious doctrine of duty faith, which not only contradicts the necessity of regeneration, but undermines the covenantal warrant for those who exercise saving faith. This gracious covenant certainly doesn’t damn sinners to hell if they reject the gospel, for not only does the very term gospel mean good news (not bad news), and not only is the whole nature of the gospel good news, but the unregenerate are damned to hell on account of their rebellion against God under the terms and promises of the Covenant of Works. Henceforth, the members of the human race are under one or the other of these two covenants. Unregenerate sinners, both the elect and the non-elect, come into this world under the authority of the Covenant of Works and are accountable to God to perfectly obey the law inscribed upon their hearts. However, once the Spirit of God regenerates His elect people, they are delivered from the authority and curse of the Covenant of Works, being brought experientially under the authority and blessings of the Covenant of Redemption. And, by virtue of the new birth, the regenerate sinner not only receives saving faith as a gift, but having been experientially brought under the authority of the Covenant of Redemption, he/she is then, and only then, given the warrant or authority to believe on Christ to the saving of the soul.

Now, you see, this view of the Covenant of Redemption is aligned with the teachings of 2 Thessalonians 2:13,14.

God the Father assumes the role of electing love from eternity. He has from the beginning chosen His people to salvation; and in time, throughout the course of history, He calls His elect people by the gospel, through the sanctifying power of the Holy Spirit. What is the sanctifying power of the Holy Spirit? It is the Spirit of God regenerating the elect according to His effectual power, uniting their souls with Christ, whereby the life of Christ flows into their souls, making them alive unto God, and the virtues of Christ flows into their souls, among which is saving faith and godly repentance. You see, it is through the sanctification of the Holy Spirit that the regenerate sinner is able to believe the truth. But what truth does the regenerate sinner believe? It is the truth of Christ’s redeeming grace, wherein He has procured for His people pardon and forgiveness of sins, true and perfect righteousness by His obedience to the law, in short, all spiritual blessings in heavenly places in Christ Jesus. It is in this way the TriUne Jehovah has prepared His people unto glory—that they might obtain the glory of the Lord Jesus Christ. This is the Covenant of Redemption, which I choose to call the Covenant of Grace. It has absolutely nothing to do with that Covenant of Grace referred to by Calvin, or Bullinger, or outlined in the 1646 Westminster Confession or preached by Sproul or written about by Berkhof. No, no. This is a very different gospel than that set forth by the 1646 Westminster Confession and the Presbyterians. What I call the Covenant of Grace is the Covenant of Redemption, fully developed to include the saving work of the TriUne Jehovah on behalf of Their elect people. And that is precisely what men such as Benjamin Keach and John Gill meant when they spoke of the Covenant of Grace.

Alright, well I hope what I’ve presented to you in this study has been of some help in your journey with the Lord. For our next study, I look forward presenting to you the covenantal view of the Reformed Baptists, represented by the 1689 Baptist Confession of Faith. I will then introduce to you a Presbyterian theologian named Thomas Boston, whose view on covenant theology, though on the surface appears to resemble that of Keach and Gill, was actually quite different, and therefore, as we unfold the development of covenant theology during the 18th century, it is helpful to compare his view to that of Keach and Gill.

Alright, more of that next week. Until we meet again, may you know the blessings of the Lord.

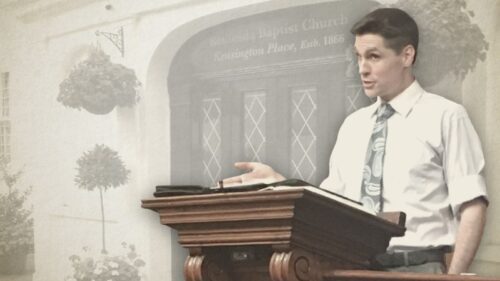

Jared Smith served twenty years as pastor of a Strict and Particular Baptist church in Kensington (London, England). He now serves as an Evangelist in the Philippines, preaching the gospel, organizing churches and training gospel preachers.

Jared Smith's Online Worship Services

Jared Smith's Sermons

Jared Smith on the Gospel Message

Jared Smith on the Biblical Covenants

Jared Smith on 18th Century Covenant Theology (Hyper-Calvinism)

Jared Smith on the Gospel Law

Jared Smith on Bible Doctrine

Jared Smith on Bible Reading

Jared Smith's Hymn Studies

Jared Smith on Eldership

Jared Smith's Studies In Genesis

Jared Smith's Studies in Romans

Jared Smith on Various Issues

Jared Smith, Covenant Baptist Church, Philippines

Jared Smith's Maternal Ancestry (Complete)