5 Umasking The Myths Of The Reformed Baptist Movement

I would like to welcome you back to another study in the Word of God. Well, actually, this study will be more of a history lesson, than a Bible exposition, but it forms part of the series of studies we started about a month ago, on an exposition of 2 Thessalonians 2:13-17. The text is divided into four main sections—a twofold statement on the privilege of brotherhood, and a twofold statement of the gospel of salvation. It is with regard to the first statement on the gospel of salvation that has led me to bring some extra studies on the subject of covenant theology. As you can see, the Apostle Paul highlights three branches of the gracious covenant in verses 13 and 14—the electing love of the Father, the redeeming grace of the Son and the sanctifying power of the Holy Spirit. Now, this is what Benjamin Keach and John Gill identified as the Covenant of Grace, and it would become the basis for the tenets of Hyper-Calvinism during the 18th century. However, this is certainly a very different framework of covenant theology than that embraced by the Presbyterians and the Reformed Baptists, represented by the leading confessional statements of the 17th century. You see, according to the covenantal framework of the 17th century, the Covenant of Grace is an agreement between God and sinners in time, with salvation offered on condition of saving faith. Whereas according to the covenantal framework of the 18th century, the Covenant of Grace is an agreement between the three Persons of the Godhead from eternity, with salvation given on condition of the Son and Holy Spirit’s work in redemption and sanctification, as set forth in our text, 2 Thessalonians 2:13,14. Now, it must be pointed out that both covenantal frameworks were embraced by the Particular Baptists. The covenantal framework of the 17th century is that which is found in the 1689 Confession, and was at that time the mainstream view of the churches. However, the covenantal framework of the 18th century is that which was introduced by Benjamin Keach and developed by men such as John Gill, which became the mainstream view of the churches during the 1700s onwards. However, 70 years ago there emerged a new group which from the beginning of their movement self-identified as Reformed Baptists. Although they did not represent the Particular Baptist denomination at the time of their emergence, they very quickly took over many of the historic chapels, and by subscribing to the 1689 Baptist Confession, laid claim to the teachings, history and heritage of the Particular Baptists. Forthwith, they have spent the last 70 years rewriting the history of the Particular Baptist denomination in an effort to give themselves a historic identity and to promote their ideology under the guise of historic precedence.

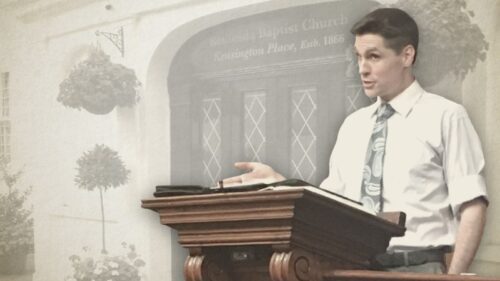

Well, I belong to the historic witness of the Particular Baptist denomination. I became a member of a Strict and Particular Baptist church in 1986 and then served as the pastor for that church between 1999 and 2019. The congregation was organized in 1866, subscribing to the covenantalism of the 18th century. It never identified as a Reformed Baptist church, nor was I ever a Reformed Baptist preacher. Nor was this church and I alone in this matter, for there remains today historic Particular Baptist churches, who have never been part of or identified with the Reformed Baptist movement. And you see, we who belong to these historic churches—understanding our teachings, history and heritage—know very well the differences between ourselves and the Reformed Baptist movement. And yet, if you do a Google search on the key words “Particular Baptists” and/or “Reformed Baptists”, the results will tell you that the two groups are one and the same. Likewise, if you watch the podcasts put out by the Reformed Baptists, and listen to their sermons and read their books, they will tell you that they represent the Particular Baptist denomination.

My dear friends, however much it may vex you to hear, this claim and common belief is certainly not supported by the facts of history. Henceforth, prior to bringing a study on the covenantal teachings of the Reformed Baptists, I wish to focus in this study on their origin and history, unmasking the myths of the Reformed Baptist movement.

Turning now to the subject at hand, a good place to begin is with the narrative created by the Reformed Baptists concerning the origin and history of the Particular Baptists. According to the Reformed Baptists, there has only been one mainstream group of the Particular Baptist churches, beginning in 1633 with the first church organized and continuing to this day. The mainstream churches have always represented the tenets of Moderate-Calvinism, subscribing to the 1689 Confession, and today they are called either Particular Baptists or Reformed Baptists. However, based on some of the extreme views of men such as John Gill, there was a fanatical group of churches that emerged during the first half of the 18th century. They became known as Hyper-Calvinists. Now, although they represented at the time a sizable grouping of the Particular Baptist churches, yet they never represented the mainstream view of the churches, nor are they at present a relevant part of the Particular Baptist heritage. You see, from the 18th century onwards, they have been in a steady decline insomuch that there is only a remnant of them that remain today. And, although their teachings are heretical and dangerous, and one must always be on guard against the heresy of Hyper-Calvinism, yet they no longer pose the threat they once did, and are therefore more of a nuisance than a menace, for they have left a dirty stain on the broader witness of the Particular Baptist churches throughout the centuries.

Now, this is the type of narrative you will invariably find presented by the Reformed Baptists. However, it is what I call the Propagandist View of History. Propaganda is information, especially of a biased or misleading nature, used to promote a particular cause, doctrine, or point of view. That is precisely what the Reformed Baptists have done. They have created a historic narrative which supports their ideology and promotes their cause, but in doing so, they have violated the fundamental laws of historicism. First, the historian must interpret history by placing the facts within their proper context. The Reformed Baptists have not done this. They have placed the facts within the context of their ideology, thereby coloring, or shading, everything with that one brush. Second, the historian must interpret history by placing all of the facts within their proper context. Again, the Reformed Baptists have done done this. They have been selective with the facts. While including those things which support their ideology, they suppress those things which contradict their predetermined narrative. The Reformed Baptists are therefore not only ahistorical, for this is the word used of those who do not interpret history within its proper context, but they are also guilty of historical negationism, which is the word used of those who ignore various facts which to do not support their desired narrative. Now, if there were histories produced on the Particular Baptists which honored the basic principles of historicism, then the propaganda put out by the Reformed Baptists would not pose so much of a problem. But, since the vast majority of recent publications over the last thirty to forty years have come from the writings of propagandists, their narratives are now embraced as fact, with relatively few inquisitive minds questioning the authenticity and accuracy of the reports. My dear friends, in eight years from now, the Particular Baptist denomination will celebrate its 400th anniversary. There has never been a more urgent need than now, for histories to be written on the teachings and chronicles of the Particular Baptist churches, honoring the basic principles of historicism, that there may be an accurate accounting of their heritage, legacy and future witness. To produce such works, within the context of so much propaganda pervading modern literature, is called historical revisionism, which is the process of setting straight the errors of the propagandists. And that is the job before me in this study.

It is now my turn to provide an overview of the facts as they relate to the history of the Particular Baptist churches. And, an overview of the facts is all I have time to give in this study. While there is a complexity to the history, in broad strokes, it can be reduced to the following time stream. Between the years 1633-1720, the mainstream churches embraced the tenets of Moderate-Calvinism. However, there was a transition between the years 1690 and 1720, with the Particular Baptists introducing and developing a series of reforms to covenant theology, leading to the tenets of Hyper-Calvinism. Forthwith, between the years 1720 and 1785, the mainstream view became that of Hyper-Calvinism. However, after Andrew Fuller published his book, “The Gospel Worthy Of All Acceptation” in the year 1785, the Particular Baptist churches began to split into two distinguishable groups. Both groups were mainstream between the years 1785-1900, with churches on both sides—the Hyper-Calvinists and the Moderate-Calvinists—being organized and thriving in number. However, under the auspices of the Metropolitan Tabernacle (although at that time, it went by a different name), John Rippon, the pastor, became one of the leaders who helped organize the Baptist Union in the year 1813. Almost all of the Moderate-Calvinist churches, represented by the teachings of Andrew Fuller, eventually joined the Union. Although it was founded upon the tenets of Moderate-Calvinism set forth in the 1689 Confession, within thirty years the Baptist Union changed the doctrinal statement in an effort to unite the General or Arminian Baptists under the same umbrella. And then, towards the end of the 19th century, the Baptist Union changed the doctrinal statement again, in an effort to unite the liberal Baptist churches under the same canopy. This led to the Downgrade Controversy, ending with Spurgeon pulling the Metropolitan Tabernacle out from the Union. Only a handful of other Moderate-Calvinist churches followed Spurgeon’s lead. The others remained in the Union, and by the year 1950, the churches had devolved into free will Arminianism and theological liberalism. Henceforth, by the 1950s, the only Particular Baptist churches representing the Moderate-Calvinist section of the denomination was the Metropolitan Tabernacle with a handful of others scattered around the country. In other words, apart from a few exceptions, this section of the denomination ended. The Hyper-Calvinist churches, on the other hand, remained separate from the Baptist Union, maintaining their doctrinal fidelity to sovereign grace. By the 1950s, there were over 400 chapels, all belonging to the Hyper-Calvinist section of the churches. This, my dear friends,—that of Hyper-Calvinism—was the mainstream view of the Particular Baptists during the mid-20th century, when the Reformed Baptist movement emerged. It was the only section remaining of the Particular Baptist denomination. Of course, the Reformed Baptist movement did not represent the soteriological or ecclesiological views of these Hyper-Calvinist churches, so they certainly didn’t belong to or represent the Particular Baptist denomination. Where then did the Reformed Baptists come from and why do they claim to represent the Particular Baptist churches? Well, to answer that question, I must give a more detailed sketch of the 1950s, when the Reformed Baptist movement emerged.

As I’ve said, the only section of the Particular Baptist denomination during the 1950s was that of the Gillite churches, or the Hyper-Calvinists. When I say Gillite churches, I mean they subscribed to the teachings of John Gill—18th century covenantalism. The other section of the Particular Baptists—that of the Fullerites or Moderate-Calvinists—these churches, having joined the Baptist Union, had become Arminian and/or liberal causes. And of course, when I say Fullerte churches, I mean they were the followers and subscribers to the teachings of Andrew Fuller—in essence, 17th century covenantalism. Now, there were exceptions to the rule. The Metropolitan Tabernacle, for instance, with a few other churches, pulled out from the Union, but there were so few of these churches, they could hardly be considered a recognizable section or branch of the Particular Baptist denomination. Even the early Reformed Baptists during the 1950s acknowledged this fact. They spoke about the Moderate-Calvinist section of the Particular Baptist denomination as no longer existing, or having descended into Arminianism.

It was the Gillette churches—the Hyper-Calvinist section of the Particular Baptists—which represented the denomination during the 1950s. There were at that time around 450 chapels. Although the congregations for the most part remained independent of Associations, they did affiliate with the various Baptist magazines in circulation at the time, such as the Gospel Standard, the Gospel Herald and Earthen Vessel and the Christian Pathway. And about one fourth of the churches belonged to one of three regional Associations. Half the churches were identified with the Gospel Standard, by far the most conservative and stedfast in their teachings; the other half were identified with the other magazines and Associations, less committed to their doctrinal fidelity. This is important to note, because I will return to these churches in a few moments, explaining how many of them departed from their founding principles.

Now, according to the Reformed Baptists, these churches—450 chapels—had fallen into Hyper-Calvinism. That is the expression and language they use to describe the churches belonging to this section of the Particular Baptist denomination. They say the churches had fallen into Hyper-Calvinism. In other words, the Reformed Baptists assert that these churches were originally founded upon the tenets of Moderate-Calvinism, subscribing to the 1689 Baptist Confession, but at some point they changed their teachings; they fell into Hyper-Calvinism. But then, when the Reformed Baptists came along during the 1950s, they rescued the churches from their Hyper-Calvinism. They reformed the churches to the truth. They restored the churches to the tenets of Moderate-Calvinism. This is what the Reformed Baptists believe.

Well, my dear friends, it is utter nonsense. You see, the vast majority of the Gillite churches had been organized and established upon the tenets of Hyper-Calvinism. They were never affiliated with the Moderate-Calvinists. And, even those historic congregations that could trace their origin to the 17th century, and therefore were founded upon Moderate-Calvinist teachings, they adopted the tenets of Hyper-Calvinism during the 18th century, which means for a few hundred years they were committed Hyper-Calvinists thriving during that time. It is a falsehood to say the Hyper-Calvinist section of the Particular Baptists had fallen into Hyper-Calvinism, and that the Reformed Baptists came to the rescue, restoring the churches to their former glory. In fact, I must say, what an inflated view the Reformed Baptists have of themselves. To present themselves, contrary to the facts, as the savior’s of the Hyper-Calvinist section of the Particular Baptist denomination.

In any case, coming back to the 450 Hyper-Calvinist churches. By the mid-20th century, after two world wars and a cultural shift towards atheism and secularism, these congregations were in serious decline. But this was also true of churches belonging to all other denominations in England. Even the Metropolitan Tabernacle was in decline. The membership of that church was so few, it could fill the first two front pews, in a chapel that could seat hundreds. Nevertheless, the Particular Baptist denomination was in decline, and as a result, there was a falling away of some of these churches and their pastors towards that of Moderate-Calvinism. These churches were abandoning the doctrinal standard upon which they had been organized. But then we must ask, why were these churches abandoning the tenets of Hyper-Calvinism?

At this point, I want to acknowledge that there are legitimate criticisms that can and should be brought against these Hyper-Calvinist churches. I am not one to glaze over the facts and pretend all was well with this group of churches, or that they did all they could have done to prevent their decline. There are certainly things they failed to do, and things they could have done better, and I have highlighted many of them in previous articles and studies I’ve given on the subject. However, before I mention one of the leading factors for the decline of these churches, it is important to address the illegitimate criticisms—the unfounded allegations—brought against these churches by the Reformed Baptists. According to the Reformed Baptists, these Hyper-Calvinist churches were in decline because of their Hyper-Calvinism. They argue Hyper-Calvinism kills evangelism, and with it the life and vitality of the churches. Whereas Moderate-Calvinism encourages evangelism, and with it the revival of the churches. In this way, they can glorify their Moderate-Calvinism by vilifying Hyper-Calvinism. Now, not only is this a cowardly and underhanded way of rejecting a set of teachings with which they disagree, but their assessment and allegation is entirely unfounded. They have absolutely no historical evidence or biblical support to back up this railing accusation against the tenets of Hyper-Calvinism.

The facts are these. The majority of these Hyper-Calvinist churches were founded upon the tenets of Hyper-Calvinism, throughout the course of the 18th and 19th centuries, which means the gospel was being preached freely to all and churches were being organized during a two hundred year period. These churches multiplied and thrived under the tenets of Hyper-Calvinism. They did not suffer an existential threat during the 18th century, nor did they suffer it during the 19th century. It was only at this point, during the mid-20th century, that the churches were facing a serious crisis. Henceforth, if Hyper-Calvinism kills evangelism and is the cause of a church’s decline, how does that assessment and allegation align with these facts of history? It doesn’t. This is a false charge brought against the tenets of Hyper-Calvinism, and I say, therefore, the Reformed Baptists are guilty of historical negationism, attempting to suppress some facts while interpreting others in a way that is favorable to their ideology and prejudices.

What then was the cause for the decline of these churches? Well, there were many factors—far too many to mention in this single study—but one of the leading causes for their decline was the style of preaching the pastors and itinerate ministers adopted towards the end of the 19th century and the first half of the 20th century. It was a style of preaching called experiential—experiential preaching. It focused primarily upon the subjective experiences of the Lord’s people, dissecting the heart and exploring the intricate avenues of one’s burden, and guilt and abhorrence of sin. It also magnified the grace of God in Christ, showing how the Lord Jesus is the perfect, glorious and only Savior for needy sinners. Now don’t get me wrong, this type of preaching brings great comfort and relief to those who are brought to know the sinfulness of their hearts. But the criticism is this—it lacked proper Bible exposition and said nothing with regards to systematic theology. And of course, this type of preaching is effective when gospel ministers understand systematic theology and know why they subscribe to the tenets of Hyper-Calvinism, for then there is substance in the preacher’s mind which propels his heart in an experiential proclamation of the gospel. However, if the preacher does not understand systematic theology or appreciate the tenets of Hyper-Calvinism, experiential preaching of this kind is much less effective and in fact, can be quite unprofitable. Now you see, there had come up among the Hyper-Calvinist churches a generation who had not been taught theology and the tenets of Hyper-Calvinism. This was true not only of those sitting in the pews, but those who were beginning to preach. And, since the pew never rises higher than the pulpit, an ignorance of doctrine began to take root among the preachers and the churches. The result? It is safe to say, by the end of the first quarter of the 20th century, there was a generation of Hyper-Calvinist churches (preachers included) who were ignorant of theology and ill equipped to represent the teachings of their fore-parents. And then, by the mid-20th century, there was a slipping away of many preachers and churches from the old paths. They became disillusioned, believing Hyper-Calvinism, or what they thought was Hyper-Calvinism, to be the cause of the Particular Baptists’ decline. And you see, because these preachers were searching for guidance, and finding no one among the Hyper-Calvinist churches to teach them, they came under the influence and teachings of preachers belonging to other denominations. Among them, and perhaps the most influential of them, was a Congregational preacher named Martyn Lloyd-Jones.

Now, Martyn Lloyd-Jones was not a Baptist, but he was a staunch Moderate-Calvinist, and was quite gifted in articulating his views. He spoke with an authority that surpassed many of his peers, undergirding his teachings not only with a grasp of church history, but combining basic Bible teachings with logic and persuasive arguments. Men such as John Doggett, who actually started out as a Hyper-Calvinist preacher among the Particular Baptists, came to denounce the tenets of Hyper-Calvinism, and this was based largely on the influence and teaching ministry of Lloyd-Jones. There were others too, men such as Iain Murray and Erroll Hulse, who, though neither came from a Particular Baptist background, yet they organized the Banner of Truth magazine, followed by the Reformation Today magazine, which became the organ of the Reformed Baptist movement. Eventually, Erroll Hulse, whose background was that of Anglicanism, would become the pastor of an old Hyper-Calvinist Particular Baptist cause in Sussex, transforming it into a Reformed Baptist church. Iain Murray would become the assistant to Martyn Lloyd-Jones at Westminster Chapel and later on the minister of a Presbyterian church in Sydney, Australia. Thus, we have Iain Murray, a Congregationalist/Presbyterian, Erroll Hulse, an Anglican turned Baptist and John Doggett, a Hyper-Calvinist Particular Baptist turned Moderate-Calvinist, all of whom spearheaded this new Reformed Baptist movement. And note, none of them came out from the Fullerite, or Moderate-Calvinist section of the Particular Baptist churches—those churches, of course, the Reformed Baptists claim to be the mainstream Particular Baptists of the last 400 years. Nor did they focus their attention on restoring these churches to their historic Fullerite teachings. No, no. They focused on the Hyper-Calvinist section of the churches, seeking to replace their Hyper-Calvinism with a Moderate-Calvinism, justifying the takeover by describing it as a reformation. They presented themselves as bringing reforms to these churches, and because these reforms were aligned with their ideology—their Moderate-Calvinism—it was considered an honorable and worthy cause. But as I am sure you can appreciate, from the perspective of the Hyper-Calvinists, it was far from honorable or commendable. They viewed the takeover as an attack, not only upon the gospel, but upon the historic witness of these churches. They viewed what the Reformed Baptists were doing as a transformation of their churches, not a reformation.

Now, the blame cannot be laid entirely at the feet of these rogue revolutionaries—men such as Doggett, Murray and Hulse. For while they were certainly guilty of infiltrating the Hyper-Calvinist churches and turning many of them away from their historic and doctrinal roots, yet the Hyper-Calvinist preachers and churches must also answer for handing themselves over to the Reformed Baptist movement. You see, there was a simultaneous handover and takeover of the churches—the churches handing themselves over and the rogue revolutionaries taking over the churches. It is estimated by the late 1960s, between 150 to 200 of the 450 churches were aligning themselves with the Reformed Baptist movement.

There were, of course, some churches which came out from the Baptist Union and were restored as Moderate-Calvinist congregations, but they too joined the Reformed Baptist movement, thus washing away their historic identification as Particular Baptists. And then there was the Metropolitan Tabernacle, which under the pastoral ministry of Peter Masters, also amalgamated with the Reformed Baptists, transforming that historic congregation into a Reformed Baptist church. And, while the Reformed Baptists focused their attention on the takeover of the Hyper-Calvinist churches, they weren’t shy making inroads to some of the historic chapels that used to be Fullerite in teachings, successfully transforming them from Arminian to Reformed Baptist churches. And keep in mind, those who were spearheading this new Reformed Baptist movement, they emerged from various backgrounds and denominations. Henceforth, the Reformed Baptist movement was a hodgepodge of preachers, coming together from all sorts of backgrounds, but taking control of the Hyper-Calvinist churches belonging to the Particular Baptist denomination.

“But,” you say, “Are not the teachings of the Reformed Baptists the same as those of the historic Fullerite Particular Baptist churches? If so, then doesn’t this in essence link them with the Particular Baptist denomination? Doesn’t it make them one and the same with the Particular Baptists?”

No, it does not make them part of the same group, and I say that for two reasons.

First, if the Reformed Baptists restored the Fullerite section of the Particular Baptist denomination to Moderate-Calvinism, and involved themselves in those churches, then there may be a connection between the two groups. But that is not what they did. Rather, they took over the Hyper-Calvinist section of the Particular Baptist denomination, not restoring the churches to their former glory, but corrupting the churches with the watered-down gospel of Moderate-Calvinism. You see, historically speaking, these churches were opposed to Moderate-Calvinism, but the Reformed Baptists transformed them into Moderate-Calvinist causes. Henceforth, rather than representing the history and heritage of these churches, they stole their historic witness, in order to give to themselves a historic identity.

Second, the Reformed Baptists not only made changes to these churches in the area of soteriology, but also that of ecclesiology. That is, they not only changed the gospel teachings of the churches, but they also changed the congregational governance of the churches. From the outset of their movement, they rejected the polity of pastor/deacon governance, insisting the churches must be governed by a plural eldership. Although this type of governance was attempted among some of the churches during the 17th century, it was rejected by the churches from the 18th century onwards. Thus, the Particular Baptists—both the Hyper-Calvinist and the Moderate-Calvinist denominations—were overseen by a pastor-deacon governance. But when the Reformed Baptists introduced the plural eldership governance to churches, it completely changed the way they functioned.

So no, I do not believe an argument can be made that the Reformed Baptists are representative of the doctrine and practice of the Particular Baptist churches. Their doctrinal innovations transformed the historic chapels and congregations into their own image and likeness. It was an entirely new set of teachings diametrically opposed by the historic witness of the Gillite churches, and in the case of the plural elderships, it was even opposed to the historic witness of the Fullerite churches.

But you see, these Reformed Baptist pioneers were quite cunning. Rather than acknowledging their teachings were different, identifying themselves as a new group of Calvinistic churches, they covered it up, calling the changes reform. It was a brilliant term to use, because on the one hand, they could use the term innocently as a throwback to the 16th century Reformation—Reformed, or Calvinistic Baptists. But on the other hand, they could use the term perfidiously, in a modern context, seeking to reform, or change, existing churches. It is therefore not surprising, seventy years after their movement began, that this term, reformed, is the most commonly used word in their vocabulary. Everything they do or talk about has the word reformed in it. They cannot write a book, preach a sermon, produce a podcast or have a friendly discussion without talking about reformed this and reformed that. In fact, one of their favorite sayings—and of course they say it in Latin, because they also love to use Latin phrases—ecclesia reformata, semper reformanda, meaning, “the church reformed, always reforming”.

When Elna and I moved to the Philippines, one of the first things I did was reach out to local and regional pastors of all denominations, hoping to forge friendships. If it was an Arminian pastor, I naturally expected him to disagree with and oppose Calvinism. But what I wasn’t expecting was to hear horror stories about the Reformed Baptists splitting their churches. Many Arminian pastors told me their personal stories about the Reformed Baptists infiltrating their congregations, and in time, after making friendships and endearing themselves with the members, would proceed to teach their Reformed Baptist doctrines, attempting to convert the members to their view point. You see, the Reformed Baptists were on a mission to reform Arminian churches. The result? They usually split the churches, either taking over the chapels with the majority of members in agreement, or leaving the churches and taking with them the minority of members converted to their teachings. Now, I ask you my dear friends, is that what Christ has commissioned His church to do? Has He commissioned His church to go out to other churches, attempting to reform them, to change them, and ultimately splitting them? I am no Arminian, but I tell you, I respect the independency and autonomy of the Arminian churches and believe it is a travesty that anyone, especially professing Christians subscribing to sovereign grace, should enter those fellowships with an agenda to reform and divide. But you see, the Reformed Baptists from the outset have never be ones to stay in their own lane. In fact, they have never had their own lane. From the beginning, they have had to move into the lanes of other churches and denominations, taking them over and claiming their history as their own. The Reformed Baptist movement—the leaders of it—emerged out of nowhere, and with a new set of teachings, sought to impose their reforms upon existing churches. And the same thing happened in the United States. No difference. The Reformed Baptists came to America during the 1960s, successfully taking over many historic Baptist churches, remaking them in their own image and likeness. What they did in England during the 1950s, they did in America during the 1960s, and they’ve done in the Philippines during the 2000s and I suggest they have been doing it around the world for the last 70 years.

Well, I’m not yet finished. I’m almost finished, but not yet. I must now ask, where does the 1689 Confession fit into this whole picture? I ask this question, because the Reformed Baptist movement adopted the 1689 Confession for their doctrinal standard. They tell us the 1689 Confession was the doctrinal standard of the mainstream Particular Baptists throughout the centuries. They tell us it was the 1689 Confession that kept the churches grounded in an unbroken line of doctrinal integrity and continuity. They tell us this is why they are confessional—confessional Baptists—because the Particular Baptists have always been confessional.

My dear friends, this is yet another falsehood propagated by the Reformed Baptists. Not only are there no facts to support this claim, the facts contradict it. The 1689 Confession was never used by the Particular Baptists as a doctrinal standard for the denomination. It wasn’t used that way when more than a hundred churches endorsed it in 1689; it wasn’t used that way during the first three quarters of the 18th century when the mainstream Particular Baptists subscribed to Hyper-Calvinism; it wasn’t used that way when Andrew Fuller reintroduced the covenant theology of the 1689 Confession in the last quarter of the 18th century; it wasn’t even used that way when the Baptist Union was formed in 1813. In fact, I can categorically say the Hyper-Calvinist section of the Particular Baptists abandoned the 1689 Confession because they fundamentally disagreed with its covenantal framework and the tenets of Moderate-Calvinism. And, although the 1689 Confession was used by the Baptist Union when it was formed in 1813, remember, about thirty years later, they replaced it with a broader doctrinal statement hoping to attract Arminian Baptist churches to join the Union. In fact, between the years 1689 and the 1950s, the 1689 Confession, within England, had only two major reprints, one by John Rippon in 1790 and the other by Charles Spurgeon in 1855. And this is not surprising. For although both men were pastors of the same church overseen by Benjamin Keach and John Gill, yet they rejected the reforms to covenant theology made by their predecessors, and were forthwith seeking to reintroduce and enforce the covenantalism of the 17th century, represented by the 1689 Confession. Nevertheless, the new printings were never widely circulated, nor were they adopted by the Fullerite churches or its denomination. Nor did the Fullerite churches subscribe to the 1689 Confession during the first half of the 20th century, for as I have already pointed out, by the 1950s, these churches had long departed from Calvinism and conversativism. And of course, the Gillite churches certainly didn’t subscribe to the 1689 Confession, for they disagreed with its covenant theology. The 1689 Confession, therefore, was nonexistent during the 1950s. Both denominations of the Particular Baptists—the Gillites and the Fullerites—abandoned the confession, though for different reasons. Henceforth, for the Reformed Baptists to claim or boast the 1689 Confession served as a doctrinal standard for the Particular Baptist denomination throughout the centuries is nonsense—it is historical negationism. They are creating a narrative out of wishful thinking in an attempt to embellish their ideology, thereby laying claim to the historic chapels and churches belonging to the Gillite Particular Baptist denomination.

So then, again I ask, how did the Reformed Baptists come to adopt the 1689 Confession as their doctrinal statement? John Doggett—he is to be credited single handedly with introducing the 1689 Confession to the Reformed Baptist movement. In his studies and research, during the 1950s, he came across an old copy of the 1689 Confession, at one time owned by a Hyper-Calvinist Particular Baptist preacher named Charles Hemington. Having read its contents, Doggett realized the document set forth the tenets of Moderate-Calvinism—that which differed significantly from the Hyper-Calvinist teachings of the Particular Baptists. It was then he knew, the confessional statement could be used as a source of authority—historical authority—lending to the argument that the Moderate-Calvinism of the 17th century was the true Calvinism of the Particular Baptist denomination. Blowing past the overarching history of the Particular Baptists, Doggett set upon an over simplified view of the churches—a propagandist view of history— dismissing the significant reforms of the 18th century and depreciating the rich heritage and gospel testimony of the Hyper-Calvinist churches. He also knew the newly emerged Reformed Baptist movement had no parent denomination to prop it up as a legitimate movement. Those who were emerging as Reformed Baptists were either the orphans of other denominations or the prodigals of the Hyper-Calvinist churches. And therefore, the 1689 Confession would give to the Reformed Baptists a historic identity and legitimacy. And mark this down, my friends, because here is the true identity of the Reformed Baptist movement. They are the orphans of other denominations and the prodigals of the Hyper-Calvinist Particular Baptist churches.

Henceforth, by subscribing to a 17th century doctrinal statement which supports the tenets of Moderate-Calvinism, they could assume the high ground as the most authentic representatives of the Particular Baptist denomination and therefore lay claim to its heritage. It was from this vantage point, the Reformed Baptists borrowed the philosophy of Presbyterianism—they would become confessional Baptist churches. That is, the Reformed Baptist movement would be founded upon the 1689 Confession, a document that would serve as the doctrinal standard around which all Reformed Baptist churches would unite. Indeed, the early Reformed Baptists—those living during the 1960s and 1970s, spoke frequently about the philosophy of Confessionalism. However, it wasn’t until the 1990s, the expression “Confessional Baptists” began to be used, by those affiliated with the Founders Ministries in the United States. Nevertheless, the philosophy of Confessionalism was adopted as early as the 1950s by the Reformed Baptist movement. And it is one of the pillars of their movement and in each of their churches today. I just listened to a podcast yesterday with Tom Ascol, the President of the Founders Ministries, making the argument that every Reformed Baptist church has the Scriptural responsibility to be Confessional.

Now, I must point out, we have here yet another innovation of the Reformed Baptist movement, not representative of the Particular Baptists. You see, not only did Particular Baptists never make the 1689 Confession their denominational statement, nor did they ever identify as confessional Baptists. They saw themselves as Scripturalists, making the Bible their only rule of authority for doctrine and practice. Yes, they had confessional statements, but these statements were drawn up by each church or Association, and they served a subordinate function to the primary place of the Bible. But you see, unlike the Particular Baptists, the Reformed Baptists are confessional—they have elevated the 1689 Confession to a primary place of authority.

My dear friends, if you have been involved with a Reformed Baptist church for any length of time—or for even a short time—you will know what I am about to say resonates with your experience. The Reformed Baptists, particularly their preachers, are 1689 fanatics. While they like to call people like me a Hyper-Calvinist, they never take a few moments for self-reflection, to consider the possibility that they are Hyper-Confessionalists. Is there even such a thing as Hyper-Confessionalism? Yes, they are Hyper-Confessionalists. They are, as it were, intoxicated with the 1689 Confession. They are addicted to it. It is like a drug. They can’t get enough of it. They use the 1689 Confession like most Christians use the Bible—it is to them sweeter than honey and the honeycomb. It is their joy and rejoicing all day, every day and twice on Sunday. They meditate on it, pray over it, interpret Scripture by it, memorize it and defend it. They love, cherish, treasure, adore, worship the 1689 Confession. And you see, our Particular Baptist fore-parents knew nothing of that kind of confessionalism—not the Hyper-Calvinists, or the Moderate-Calvinists. In fact, if there were members of those churches idolizing a confessional statement the way the Reformed Baptist worship the 1689 Confession, they would have been censured and disciplined by the churches. While Confessionalism is a hallmark of the Reformed Baptist movement, it is not a feature of the Particular Baptist denomination, which is further evidence the two groups are entirely separate.

Alright, well, I must leave it there. It has been my purpose in this study to draw a line between the Particular Baptist denomination and the Reformed Baptist movement. There is so much misinformation floating around, propagated by the Reformed Baptists, very few people today are aware of the facts. In the weeks to come, I will open up these matters further, exploring various aspects of the Particular Baptist denomination as well as the Reformed Baptist movement, hoping these studies will serve as a help in your quest to not only understand more clearly the gospel of your salvation, but to know the history and the heritage of these churches called, Particular Baptists.

I do pray the Lord will bless to you the teachings, and, until we meet again next week, may you continue to know His presence and enjoy sweet communion with the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit.

Jared Smith served twenty years as pastor of a Strict and Particular Baptist church in Kensington (London, England). He now serves as an Evangelist in the Philippines, preaching the gospel, organizing churches and training gospel preachers.

Jared Smith's Online Worship Services

Jared Smith's Sermons

Jared Smith on the Gospel Message

Jared Smith on the Biblical Covenants

Jared Smith on 18th Century Covenant Theology (Hyper-Calvinism)

Jared Smith on the Gospel Law

Jared Smith on Bible Doctrine

Jared Smith on Bible Reading

Jared Smith's Hymn Studies

Jared Smith on Eldership

Jared Smith's Studies In Genesis

Jared Smith's Studies in Romans

Jared Smith on Various Issues

Jared Smith, Covenant Baptist Church, Philippines

Jared Smith's Maternal Ancestry (Complete)