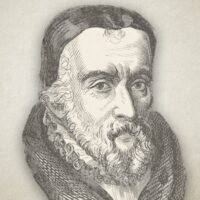

The Life And Ministry Of William Tyndale

Ken Connolly, “The Church In Transition”, Page 73:

William Tyndale was actually born as William Hychyns, near the Welsh border in Gloustershire, in the year 1494. He later registered at Magdalen Hall in Oxford as William Hychyns. We know very little about his family, except that he had two brothers, John and Edward.

Hychyns/Tyndale graduated with a Master’s degree in 1515, and spent the next four years in Oxford. The very next year, Erasmus, who had previously spent three years lecturing at Oxford, published his Greek New Testament. Erasmus “Novium Instrumentum” began to take rival Cambridge by storm. The spiritual climate at Oxford was such that it would be another eight years before anyone would lecture from the Bible. Therefore, in 1519, William Tyndale decided to leave Oxford for Cambridge.

Tyndale immediately became associated with Thomas Bilney. and joined his White Horse Inn Bible study. The membership names in that Bible study reads like a “Who’s Who” of the Reformation. It included the names of: dark, Frith, Barnes, Ridley, and Latimer. It produced two archbishops, seven bishops, and eight martyrs. Their common experiences, and unanimous conclusions, deeply impressed William Tyndale. The members of the White Horse fellowship considered access to the Word of God, and its unquestioned authority, as mandatory for any emancipation from religious shackles.

In 1521 Tyndale left Cambridge for Little Sodbury Manor. There he became the chaplain, and tutor of the two young sons, for Sir John Walsh. The older boy was but six years of age, and Tyndale was required to teach him and his younger brother to read, write, and count. Having much free time, Tyndale spent it preaching in the neighborhood. He became increasingly impressed that the masses were untouched by the movement in Cambridge, because they were illiterate in both Greek and Latin; therefore, Tyndale became obsessed by an inward passion to provide the ordinary man with his own Bible, in the common language. However, two obstacles, stood in his way.

First, convention demanded that religion be communicated in Latin, One woman, and seven men, had been burned to death at Little Park, in Coventry, just two years previously. They were guilty of teaching their children the Lord’s Prayer, and the Ten Commandments, in English.

The second major obstacle was that a law had been passed in the previous century, because of what Wycliffe and his Lollards had done. It was no longer possible for a man to translate Scripture without the permission of a bishop. Tyndale, therefore, appealed to Dr. Cuthbert Tunstall, the bishop of London, but permission was flatly refused.

Tyndale resigned from Sodbury and moved to London, to begin his illicit assignment, hidden among the masses in that metropolitan city, John Frith, a brilliant mathematician from Oxford, came to assist Tyndale in his secret endeavor.

Tyndale only stayed in London for six months, and then, for reasons of safety, travelled to Wittenburg, Luther’s city, where he could operate without fear for his life.

Tyndale was attracted to Martin Luther, though the latter was ten years his senior. Luther had been on trial in Worms, only two years previously, and had given that unforgettable affirmation: “My conscience has been taken captive by the Word of God…Here I stand. So help me God. I can do none else.” Though the two reformers were separated by certain interpretations of Scripture, they were strongly united by the motto: “sola Scriptura” (Scripture alone). That German city of Wittenburg was a happy refuge for the English religious “outlaw.”

While Tyndale was in Wittenburg, he had several meetings with Luther, enrolled at the university under an alias, and of greatest importance, completed the translation of his New Testament. William Roye from Greenwich associated himself with Tyndale, offering to assist him in every capacity required, and to print and distribute those New Testaments.

Finding a printer, however, was not easy. Roye and Tyndale went to Hamburg, then to Cologne. In the latter city, they found one who was willing to help, but with questionable motives. Nevertheless, the pair of English reformers could not afford to be too choosy. English spies soon broke up the operation. The two men escaped from the print shop in the night with the bundles of printed manuscripts in their arms. They then found Peter Schoeffer, in Worms, who was willing to finish the task. The printing of Tyndale’s English New Testament was completed in December of 1525.

The moment that publication was smuggled into England, in the spring of 1526, it fermented national unrest. King Henry VIII condemned it to a public burning. Nevertheless, hundreds of copies were being read. People were willing to go to prison for distributing it. The English government became livid with anger. They raised money to buy up every copy circulating on the continent. They found out, however, that Tyndale knew the government agents, and, for every copy he sold them, he was able to print four. Oh, wonder of Providence. God is sovereign! William Tyndale was actually printing his English New Testament at the King’s expense.

Tyndale and Roye parted company after the Worms edition was completed. Tyndale then went to Marburg, in 1527, and added Hebrew to his linguistic skill. He actually mastered seven languages. He then proceeded to translate the Pentateuch.

Tyndale moved back to Hamburg, then to Antwerp, Belgium, and started writing pamphlets in defense of the Reformation. He renewed his acquaintances with John Frith and Miles Coverdale. For the next several years, Tyndale became a fugitive and a vagabond. He discovered what it was like to be a fox in a countryside surrounded with hounds.

When Tyndale heard of the execution of John Frith, he returned to the home of Thomas Poyntz, in Antwerp. Poyntz was a relative of Mrs. Walsh from Little Sodbury. Tyndale stayed at Poyntz’ home and revised his New Testament. Unfortunately, he could not stay to supervise the editing and printing, and it circulated fall of printing errors, in 1534.

Tyndale returned to Poyntz’ home, and met Harry Phillips, from England, in 1535. It was Phillips who betrayed his identity. Tyndale was arrested and brought to Vilvorde Castle, only six miles from Brussels. There he was imprisoned. All efforts made for his release or escape failed. William Tyndale was tried in August, 1536, then in October of the next year he was tied to a stake, strangled as an act of mercy, and then burned as a heretic.

Ironically, Miles Coverdale and John Rogers submitted a New Testament, in English, for the approval of the king. On September 5, 1538, the king ordered the printers to supply a copy to every church in England . It was to be available for reading, in every community in England. The single copy in each church was chained in place. That chained Bible became very popular. People even read it aloud while Masses were being conducted. In actual fact, that Bible was William Tyndale’s New Testament, virtually unchanged!

William Tyndale (1494-1536) was a sovereign grace preacher during the Protestant Reformation, a biblical scholar and linguist. He is best known for translating the Greek New Testament into English and overseeing its printing, publication and distribution. His work became the foundation for subsequent translations, such as the Coverdale Bible (1535), Matthew’s Bible (1537), Great Bible (1539), Bishop’s Bible (1568), Geneva Bible (1560) and the Authorized Version (1611). It is estimated the King James Translation retains 80% of Tyndale’s work.